In the past few days a lot of people, especially journalists, have been publicly reassessing the lab leak theory and admitting that maybe it deserved more fair-minded attention than it initially received. This doesn’t mean the theory is true of course. Someone may yet turn up a plausible animal candidate to explain the zoonotic transfer from bats to humans. What has happened though is a change in the conventional wisdom about the possibility of a lab leak.

For months, starting early last year, anyone who mentioned the lab leak theory was ridiculed and treated as the modern equivalent of a flat-earther. That didn’t happen by accident. It happened partly because of a handful of motivated scientists and partly because the media was eager, as always, to write stories saying Republicans were spectacularly wrong. Yesterday Jonathan Chait wrote a summary of how this media crusade against the lab leak theory got started. The first mentions of the story appeared in the Daily Mail and the Washington Times. Thus the stage was set for a mainstream media backlash to begin.

In January 2020, the Washington Post wrote a story headlined, “Experts debunk fringe theory linking China’s coronavirus to weapons research.” This piece correctly refuted the claim that the virus was deliberately manufactured as a biological weapon. It did not distinguish the (highly unlikely) bioweapon theory from the related, more plausible theory that the disease escaped from the Wuhan lab without ever having been intended as a weapon. More damagingly, this story treated the Wuhan lab’s security as essentially impregnable, asserting that “the Wuhan National Biosafety Laboratory is a ‘Cellular Level Biosafety Level 4’ facility, which means it has a high level of operational security and is authorized to work on dangerous pathogens, including Ebola.”…

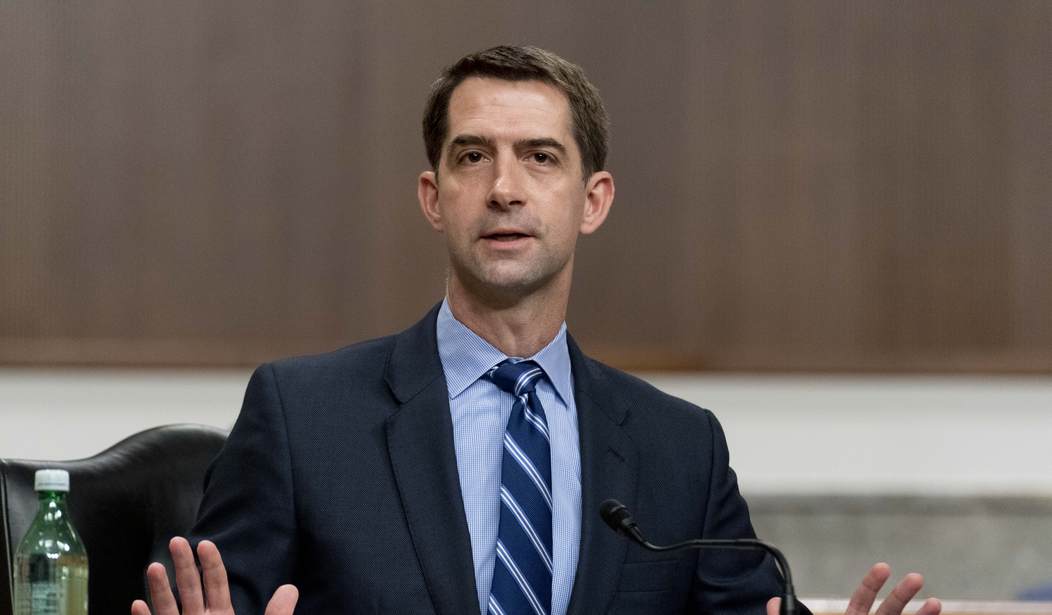

In February, Senator Tom Cotton appeared on television to raise questions about what China was hiding. Cotton kept his exact accusation vague, perhaps deliberately. “We don’t have evidence that this disease originated there,” he said of the Wuhan lab, “but because of China’s duplicity and dishonesty from the beginning, we need to at least ask the question to see what the evidence says, and China right now is not giving evidence on that question at all.”

Reporters immediately began accusing him of promoting the most extreme version of Trump’s charge. The New York Times labeled Cotton’s remarks a “conspiracy theory.” The Washington Post’s account was headlined, “Tom Cotton keeps repeating a coronavirus conspiracy theory that was already debunked.” The Post quoted an expert denying the virus “was a deliberately released bioweapon,” but Cotton hadn’t said that.

Today the Post’s fact-checker released a timeline of the lab leak theory. The Daily Mail and Washington Times stories mentioned above get their own bullet points in this timeline but curiously the Post’s response on January 29 isn’t mentioned even though that was clearly one of the first major stories to push the idea that the lab leak was a conspiracy theory. A subsequent story aimed more directly at refuting Sen. Tom Cotton’s statements about a lab leak linked back to that piece in it’s first line:

Sen. Tom Cotton (R-Ark.) repeated a fringe theory suggesting that the ongoing spread of a coronavirus is connected to research in the disease-ravaged epicenter of Wuhan, China.

The Post story went on to describe Sen. Cotton’s (outrageous?) demand that China answer questions about the possibility of a lab leak:

Yet Cotton acknowledged there is no evidence that the disease originated at the lab. Instead, he suggested it’s necessary to ask Chinese authorities about the possibility, fanning the embers of a conspiracy theory that has been repeatedly debunked by experts.

In retrospect, it’s not Sen. Cotton’s position that seems outrageous but the Post’s suggestion that demanding answers from Chinese authorities is fanning the flames of a conspiracy theory. And that’s true whether or not the lab leak theory winds up to be true or false. The point is that, in February 2020, we really didn’t have much evidence either way and a year later we still don’t have conclusive proof. So shutting down the discussion in January or February of 2020 didn’t make a lot of sense.

Read through the rest of the Post’s timeline and you’ll see what eventually happens is a few people take a closer look at the question and find that, while it’s still a minority view among scientists, it can’t be totally ruled out.

Looking back, it was really the Washington Post that pushed back hardest on this possibility but even the timeline published today doesn’t quite make that clear because it fails to give this story its own bullet point in the developing narrative.

Ultimately we may never know for certain what happened because so much time has passed. The real downside to having a stifled public conversation about the possibility of a lab leak is that China was never really pressed to answer questions. Instead we spent a full year being scolded by the media for a) questioning the origin story of the virus and b) calling it a “Chinese virus” even as Chinese authorities were suggesting it was an American virus.

Meanwhile, it took a year for WHO to get a team of scientists to Wuhan and even then it was a team with no real ability to investigate anything, only to ask questions of their Chinese counterparts who are no doubt aware of what happens to those who fail to toe the party line.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member