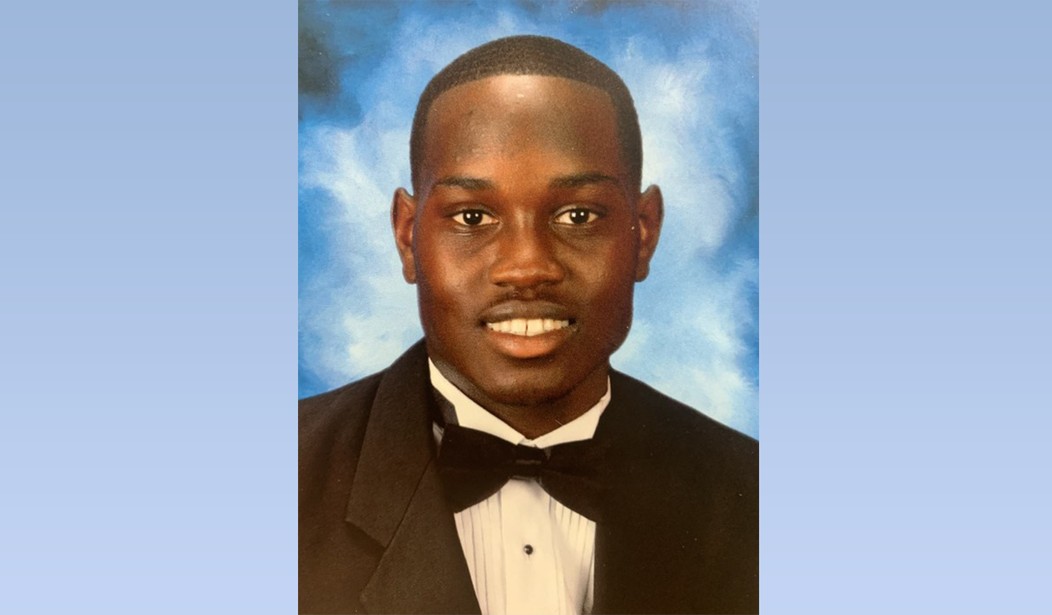

When jury selection began in the murder trial of Greg and Travis McMichael, along with Roddy Bryan for the death of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia last year, we examined some of the potential problems awaiting the court in finding the right jury to hear the case. The challenges seemed so obvious that one local attorney opined that the entire trial was going to be won or lost during voir dire. The jury pool is being pulled from a community that has been torn apart by this case for almost two years, and finding someone who doesn’t already know about it is virtually impossible. Identifying anyone who doesn’t already have a preconceived opinion about what happened was going to be almost as challenging.

Those predictions appear to be playing out and there’s not much anyone can do about it. According to the Associated Press, the court has already interviewed more than seventy prospective jurors. Many had to be discharged due to personal hardship reasons or “unshakable bias,” leaving them with only 23 thus far who advanced to the next phase. They expect to continue interviews all through the coming week. But some of the ones who have been allowed to advance already will put the “unshakable bias” theory to the test.

No. 218 joined a bike ride supporting Ahmaud Arbery’s family after the young Black man was chased down and shot dead. No. 236 was a longtime co-worker of one of the white men charged in the killing.

Identified in court only by numbers, both people were summoned to jury duty in the trial over Arbery’s slaying. And after attorneys questioned them extensively about the case, the judge deemed both to be fair-minded enough to remain in the pool from which a final jury will be picked…

The judge, prosecutors and defense attorneys have questioned 71 pool members since jury selection began Monday. After dismissing those with personal hardships or unshakable biases, 23 were deemed qualified to advance. Dozens more will be needed before a final jury of 12 plus four alternates can be seated.

One of the prosecutors, Linda Dunikoski, has been telling the candidates that the ideal juror would be someone with a “blank slate” in terms of the death of Ahmaud Arbery. But she’s also admitted to them that finding someone like that is “probably impossible” so they are dealing with what they have.

Under Georgia law, a juror is allowed to arrive “with an opinion about the case, as long as that person expresses a willingness to keep an open mind.” That’s a fairly low bar to set if we’re being honest about this. Anyone can say that they’ll have an open mind and then it’s up to the court to try to read their minds and determine if they are sincere or they are just trying to get on the jury to help “their side.” The people admitting that they have such a fixed opinion that no evidence could sway them either way are probably just looking to get out of jury duty.

Take the two examples that the AP cites in the excerpt above. One of them was a “longtime co-worker” of one of the defendants, though we’re not told which one. I suppose that doesn’t mean the end of the world because simply working for the same employer, particularly if it’s a large organization, doesn’t mean you were necessarily a friend of theirs. In fact, you might not have liked them at all. But it’s still risky to use them.

The other one seems even worse as a choice. Is someone who was motivated enough to show up for a bike rally in support of the Arbery family and display “Justice for Ahmaud” signs really still be on the fence about what happened? It just strikes me as unlikely. And yet both of them moved on to the next stage. That doesn’t mean either of them will actually make it onto the jury because both the prosecution and the defense are allowed a set number of peremptory challenges where they can reject potential jurors without cause. But that really thins down the pool near the end.

Juror number 218 wrote on her jury summons response form, “a young man was shot due to his color, and the three men that committed the act almost got away.” But she’s one of the ones who are still in the running for a seat. Shouldn’t that be worrisome?

In the end, divided jury pools like this almost always work out in the favor of the defense. The reason for this is simple. The prosecution has to find twelve people (plus four alternates) who are willing to consider voting to convict. The defense only has to find one that will refuse no matter what happens. At least thus far, it doesn’t sound like the prosecution is going to bat 16 for 16 here.