Will NCAA athletes start receiving pay for their entertainment value to colleges and universities? Not necessarily, but the NCAA just lost significant authority to prevent it. In a unanimous decision today, the Supreme Court ruled that the NCAA operates as a monopoly that unfairly limits compensation to and competition for star athletes.

This could revolutionize college sports, the Wall Street Journal notes:

The Supreme Court on Monday ruled that strict NCAA limits on compensating college athletes violate U.S. antitrust law, a decision that could have broad ramifications for the future of college sports.

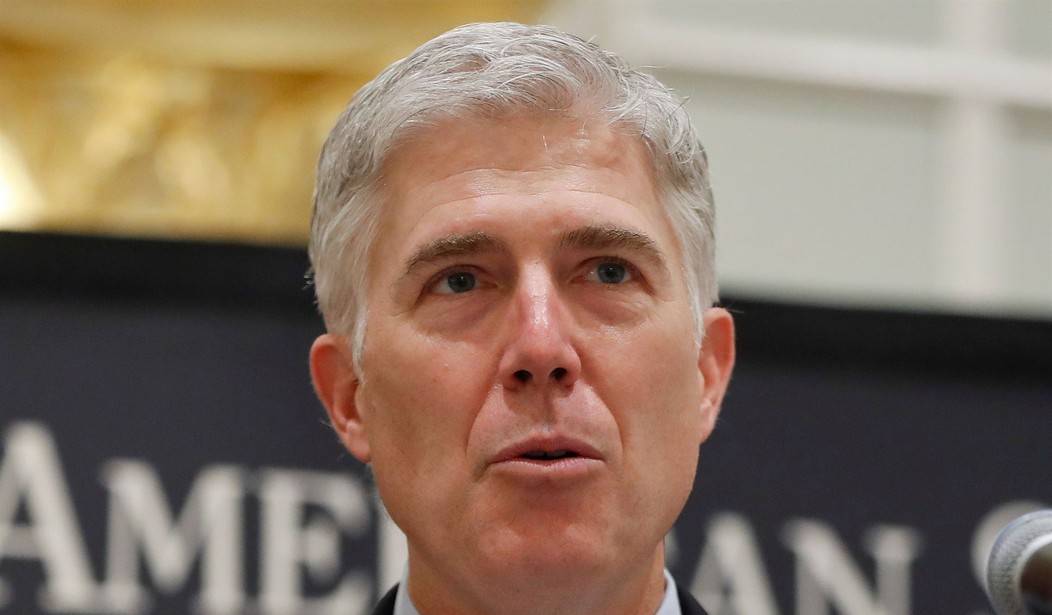

The court, in a unanimous opinion by Justice Neil Gorsuch, upheld lower court rulings that said the NCAA unlawfully limited schools from competing for player talent by offering better benefits, to the detriment of college athletes.

The court’s decision comes at a pivotal moment in the broader fight over athletes’ ability to be paid for their participation in the college-sports juggernaut.

Various state laws allowing athletes to earn money from the use of their name, image and likeness are coming into effect as soon as July 1. Their number is growing every week as state legislatures rush them through in the fear their universities will lose out on prized recruits without such laws in place.

The ruling doesn’t directly address payment for athletic performance. However, Justice Neil Gorsuch takes direct aim at the NCAA’s de facto monopoly power, which itself might be the main obstacle for states inclined to allow it:

In applying the rule of reason, the district court began by observing that the NCAA enjoys “near complete dominance of, and exercise[s] monopsony power in, the relevant market”—which it defined as the market for “athletic services in men’s and women’s Division I basketball and FBS football, wherein each class member participates in his or her sport-specific market.” D. Ct. Op., at 1097. The “most talented athletes are concentrated” in the “markets for Division I basketball and FBS football.” Id., at 1067. There are no “viable substitutes,” as the “NCAA’s Division I essentially is the relevant market for elite college football and basketball.” Id., at 1067, 1070. In short, the NCAA and its member schools have the “power to restrain student-athlete compensation in any way and at any time they wish, without any meaningful risk of diminishing their market dominance.”

The district court then proceeded to find that the NCAA’s compensation limits “produce significant anticompetitive effects in the relevant market.” Id., at 1067. Though member schools compete fiercely in recruiting student-athletes, the NCAA uses its monopsony power to “cap artificially the compensation offered to recruits.” Id., at 1097. In a market without the challenged restraints, the district court found, “competition among schools would increase in terms of the compensation they would offer to recruits, and studentathlete compensation would be higher as a result.” Id., at 1068. “Student-athletes would receive offers that would more closely match the value of their athletic services.” Ibid. And notably, the court observed, the NCAA “did not meaningfully dispute” any of this evidence. Id., at 1067; see also Tr. of Oral Arg. 31 (“[T]here’s no dispute that the—the no-pay-for-play rule imposes a significant restraint on a relevant antitrust market”).

The NCAA’s only remaining justification for protecting this monopoly power, Gorsuch writes, is the protection of amateurism in sports. However, Gorsuch points out that this amateurism is curiously targeted. The NCAA makes billions of dollars every year, he notes from the district court’s trial record, and its executives earn millions each year in compensation. That makes the restrictions on athlete compensation look pretty manipulative, if not arbitrary.

Furthermore, the district court’s remedy appears targeted and specific, Gorsuch writes:

Nothing in the order precluded the NCAA from continuing to fix compensation and benefits unrelated to education; limits on athletic scholarships, for example, remained untouched. The court enjoined the NCAA only from limiting education-related compensation or benefits that conferences and schools may provide to studentathletes playing Division I football and basketball. App. to Pet. for Cert. in No. 20–512, p. 167a, ¶1. The court’s injunction further specified that the NCAA could continue to limit cash awards for academic achievement—but only so long as those limits are no lower than the cash awards allowed for athletic achievement (currently $5,980 annually). Id., at 168a–169a, ¶5; Order Granting Motion for Clarification of Injunction in No. 4:14–md–02541, ECF Doc. 1329, pp. 5–6 (ND Cal., Dec. 30, 2020). The court added that the NCAA and its members were free to propose a definition of compensation or benefits “‘related to education.’” App. to Pet. for Cert. in No. 20–512, at 168a, ¶4. And the court explained that the NCAA was free to regulate how conferences and schools provide education-related compensation and benefits. Ibid. The court further emphasized that its injunction applied only to the NCAA and multi-conference agreements—thus allowing individual conferences (and the schools that constitute them) to impose tighter restrictions if they wish. Id., at 169a, ¶6. The district court’s injunction issued in March 2019, and took effect in August 2020.

This doesn’t mean that student-athletes can start drawing salaries. Gorsuch writes that the district court’s ruling only applies to restrictions on educational benefits and some other school-related awards. Nothing in the ruling forbids the NCAA from continuing to prohibit booster-sourced compensation for athletes:

Third, the NCAA contends that allowing schools to provide in-kind educational benefits will pose a problem. This relief focuses on allowing schools to offer scholarships for “graduate degrees” or “vocational school” and to pay for things like “computers” and “tutoring.” App. to Pet. for Cert. in No. 20–512, at 167a–168a, ¶2. But the NCAA fears schools might exploit this authority to give student-athletes “‘luxury cars’” “to get to class” and “other unnecessary or inordinately valuable items” only “nominally” related to education. Brief for Petitioner in No. 20–512, at 48–49.

Again, however, this over-reads the injunction in ways we have seen and need not belabor. Under the current decree, the NCAA is free to forbid in-kind benefits unrelated to a student’s actual education; nothing stops it from enforcing a “no Lamborghini” rule. And, again, the district court invited the NCAA to specify and later enforce rules delineating which benefits it considers legitimately related to education. To the extent the NCAA believes meaningful ambiguity really exists about the scope of its authority— regarding internships, academic awards, in-kind benefits, or anything else—it has been free to seek clarification from the district court since the court issued its injunction three years ago. The NCAA remains free to do so today. To date, the NCAA has sought clarification only once—about the precise amount at which it can cap academic awards—and the question was quickly resolved. Before conjuring hypothetical concerns in this Court, we believe it best for the NCAA to present any practically important question it has in district court first. …

Some will think the district court did not go far enough. By permitting colleges and universities to offer enhanced education-related benefits, its decision may encourage scholastic achievement and allow student-athletes a measure of compensation more consistent with the value they bring to their schools. Still, some will see this as a poor substitute for fuller relief. At the same time, others will think the district court went too far by undervaluing the social benefits associated with amateur athletics. For our part, though, we can only agree with the Ninth Circuit: “‘The national debate about amateurism in college sports is important. But our task as appellate judges is not to resolve it. Nor could we. Our task is simply to review the district court judgment through the appropriate lens of antitrust law.’” 958 F. 3d, at 1265. That review persuades us the district court acted within the law’s bounds.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s concurrence sends a signal that the court might be willing to hear a case that addresses the NCAA’s position more directly:

Price-fixing labor is price-fixing labor. And price-fixing labor is ordinarily a textbook antitrust problem because it extinguishes the free market in which individuals can otherwise obtain fair compensation for their work. See, e.g., Texaco Inc. v. Dagher, 547 U. S. 1, 5 (2006). Businesses like the NCAA cannot avoid the consequences of price-fixing labor by incorporating price-fixed labor into the definition of the product. Or to put it in more doctrinal terms, a monopsony cannot launder its price-fixing of labor by calling it product definition.

The bottom line is that the NCAA and its member colleges are suppressing the pay of student athletes who collectively generate billions of dollars in revenues for colleges every year. Those enormous sums of money flow to seemingly everyone except the student athletes. College presidents, athletic directors, coaches, conference commissioners, and NCAA executives take in six- and seven-figure salaries. Colleges build lavish new facilities. But the student athletes who generate the revenues, many of whom are African American and from lower-income backgrounds, end up with little or nothing. See Brief for African American Antitrust Lawyers as Amici Curiae 13–17.

Everyone agrees that the NCAA can require student athletes to be enrolled students in good standing. But the NCAA’s business model of using unpaid student athletes to generate billions of dollars in revenue for the colleges raises serious questions under the antitrust laws.

In other words, the writing may be on the wall for the NCAA and its selective commitment to amateurism. Still, this decision doesn’t unleash salary wars in college sports — at least not yet. The Supreme Court is for now just limiting and refining the NCAA’s ability to regulate non-monetary compensation offered by schools. That alone will undermine its monopoly power, and states may end up doing the rest.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member