How many buzzwords can one person toss into an article?

Quite a few, and if you are writing about the silliest thing to panic about in the universe you had better throw in something ominous like “tipping point.”

Generative AI has the potential to push the internet's carbon footprint to a tipping point. The many experts I spoke with disagreed on the technology's potential emissions, but even a small bump could be disastrous, for @TheAtlantichttps://t.co/37lUYNLbNx

— Matteo Wong (@matteo_wong) August 23, 2023

I am tempted to extend a bit of sympathy to the author, Matteo Wong. He looks like a nice young man, and a writer grabbing an Assistant Editor gig at The Atlantic is nothing to sneeze at. Although I can tell you that since titles are free, the less one makes the nicer they make the title sound in some industries. For instance, I am an “Associate Editor,” which in Hot Air-speak is “low man on the totem pole.”

Given the spot he is in he has to come up with something, no matter how ridiculous, to get his name on a byline.

Whatever his place on The Atlantic’s totem pole, Mr. Wong has written a doozy of a story. While most technologists rhapsodize about AI’s revolutionizing society or spread fear about its potential for extinguishing the human race, Matteo here has more down to earth fears: a climate change disaster.

Yes, ChatGPT is pushing us to a tipping point!

God I love tipping points. They allow one to warn of incredible dangers without trotting out any actual evidence. Before the tipping point there seems to be no problem. Then BOOM! Tipping point reached and disaster strikes.

Perfect for alarmism.

Right now the Internet does burn a lot of juice–4% of the world’s emissions supposedly stem from it–Matteo’s fear is that AI is going to cause computing’s carbon emissions to skyrocket. Seems unlikely, given that electricity costs money and everybody wants to save money by minimizing power consumption. But sure, more computing, all other things being equal, means more power consumption. OTOH, computing power per watt has skyrocketed. Which is why my 2021 16″ MacBook is one of the fastest laptops ever made and can last 12-18 hours on one charge. Compare that to my older laptop–7 years old–which was vastly less powerful and lasted only about 5 hours.

He admits it is hard to say how much more power will be eaten up because there are a lot of variables. Of course his ignorance allows for scary speculation!

Just imagine! There could be a tipping point somewhere. Maybe. Probably. Doom! Due to ChatGPT.

Something has to provide that tipping point. Why not AI?

While the internet accounts for just a sliver of global emissions, 4 percent at most, its footprint has steadily grown as more people have connected to the web and as the web itself has become more complex: streaming, social-media feeds, targeted ads, and more.

All of that was before the generative-AI boom. Compared with many other things we use online, ChatGPT and its brethren are unique in their power usage. AI risks making every search, scroll, click, and purchase a bit more energy intensive as Silicon Valley rushes to stuff the technology into search engines, photo-editing software, shopping and financial and writing and customer-service assistants, and just about every other digital crevice. Compounded over nearly 5 billion internet users, the toll on the climate could be enormous. “Within the near future, at least the next five years, we will see a big increase in the carbon footprint of AI,” Shaolei Ren, a computer scientist at UC Riverside, told me. Not all of the 13 experts I spoke with agreed that AI poses a major problem for the planet, but even a moderate emissions bump could be destructive. With so many of the biggest sources of emissions finally slowing as governments crack down on fossil fuels, the internet was already moving in the wrong direction. Now AI threatens to push the web’s emissions to a tipping point.

What, pray tell, does that even mean? Tipping into what? Using 5% more energy? 10%? Honestly, tipping point?

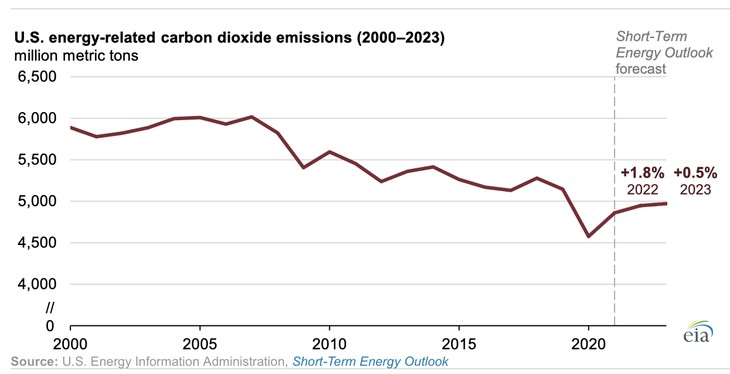

Carbon emissions in the developed world have been falling. AI, we should suppose, would accelerate the efficiency of many processes. If it takes a bit more energy to save a lot more energy that would be a good thing, right?

Well, no. Because AI helping reduce carbon dioxide still requires using energy, and that is the real problem, apparently. Anything that allows human beings to do things must be abolished, it seems.

The carbon footprint of generative AI doesn’t need to grow exponentially to threaten the planet. Meeting our ambitious climate targets will require decreasing emissions across every sector, and AI makes it much harder to stabilize, let alone shrink, the internet’s share. Even if the tonnage of carbon the internet pumps into the atmosphere didn’t budge for decades—an improbably optimistic scenario—and everything else in the world reduced its emissions enough to stop warming at 1.5 degrees Celsius, as is the goal of the Paris agreement, that would still be “nowhere near enough” to meet the target, as one 2020 opinion paper in the journal Patterns put it. As AI and other digital tools help other sectors become greener—improving the efficiency of the grid, enhancing renewable-energy design, optimizing flight routes—the internet’s emissions may continue creeping up. “If we’re using AI, and AI is being sold as pro-environment, we’re going to increase our use of AI throughout all sectors,” Gabrielle Samuel, a lecturer in environmental justice and health at King’s College London, told me.

AI could be so good that it is bad or something. Make it make sense, because for all the world it doesn’t make sense to me. How could it? If you believe that the world needs to emit less carbon into the atmosphere, it makes sense to tolerate a modest increase in emissions in one sector to provide a major reduction in another.

But since carbon is a moral, not a practical issue, we must reduce it everywhere all at once. Rationality be damned.

Because tipping points or something.

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of AI’s carbon footprint is that, because the internet’s emissions have always been relatively small, almost no one is prepared to deal with them. The Inflation Reduction Act, the historic climate law Congress passed last year, doesn’t mention the web; activists don’t chain themselves to data centers; we don’t teach children to limit their search queries or chatbot conversations for the sake of future generations. With so little research or attention given to the issue, it’s not clear that anybody should. Ideally AI, like coal-fired power plants and combustion-engine cars, would face the economic and regulatory pressure to become emissions-free. Similar to how the EPA sets emissions requirements for new vehicles, the government could create ratings or impose standards for AI model efficiency and the industry’s use of renewable-energy sources, Luccioni said. If a user asks Google to decide whether a photo is of a cat or a dog, a less energy-intensive model that is 96 percent accurate, instead of 98 percent, might suffice, Devesh Tiwari, an engineer at Northeastern University, has shown.

As you can see, we long passed the real tipping point we should worry about: the climate religion demands sacrifices to Gaia, just as the pagan gods of old did. And if the sacrifices still don’t bring the rain, the blood of a few more kids may do the trick.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member