The first time I ever set eyes on John Perry, he was about an hour old and his proud dad was pointing out his squished red face to me through the maternity ward’s glass window.

Even being born he’d managed to cause excitement. A really sharp delivery nurse noticed some spikes in his fetal monitor pulse and called the OBGYN in. Lucky thing, because the C-section revealed the umbilical cord wrapped twice around his neck. He’d have hung himself being born.

It also gave Kcruella C-section scars to hold over his head.

Kcruella and I had gone through Marine Corps bootcamp together, while my husband – major dad – and John’s dad had been stationed in TOW Company at Camp Pendleton. The four of us met going through aviation training at NAS Memphis and were fast friends almost immediately. Eventually, we also all wound up with orders to California and 3rd Marine Aircraft Wing squadrons. We girls married the guys.

Our Ebola was the first kiddo to make his debut, and his Aunt Kcruella and Uncle Stu spoiled him unmercifully. Each of the four of us worked on different airplanes, had different hours, six-month long deployments, and no family close. WE were our family. They were there for us and, 5 years later, when John entered this world, Ebola had his little brother, and we were there for them.

The two boys grew up in each other’s homes. If John was coming over, I had to make chocolate chip cookies. If Ebola was going to their house, he had to have his bike go with him. All sorts of rules. If Ebola went somewhere, or had a party, John was there with the big kids.

It was like breathing. Our normal in the chaos of active duty life.

That changed in ’92. As part of Clinton’s military drawdown, the Marine Corps offered paid get-out-of-jail-free passes to both officers and enlisted folks. Kcruella and I were both eligible and we jumped on it. What that meant for the Welborns as a couple was that, as the Corps no longer had to pay for TWO Marines to move, hubs soon had orders to the far-off foreign land of North Carolina. We left CA, and the other half of our little family, after 12 years there.

Kcruella eventually wound up back in New Jersey when things didn’t work out for them. But we still saw John damn near every year, while in North Carolina through our last set of orders to Pensacola.

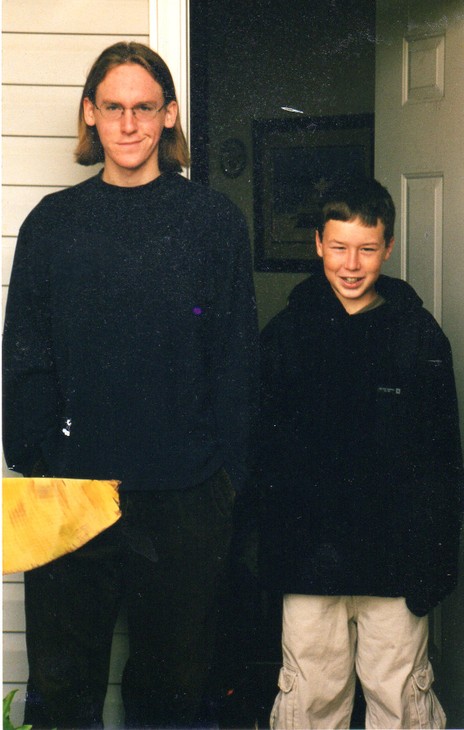

The pictures of the boys through the years are like marks on a refrigerator or a door jamb.

And then, suddenly, they’re grown up. They were young men.

How did that happen? Our babies.

John was the first to go in the service. I was lucky enough to keep his mom, grandmom and future bride company at his graduation. Such a handsome soldier boy with his mom.

Who became a superb soldier and, unsurprisingly, proved to be a natural leader. John always had the time and the knack to help make everyone around him better.

More importantly, he married that terrific girl, they traveled the world with the Army and then settled in to have two kids and live life large.

He was always an athlete – a terrific skateboarder, body surfer, fisherman. He took the time to get better every place he landed. He found lakes and big bass on Fort Hood no one even knew existed.

The whole while, he and Ebola – who had by this time enlisted in the Air Force (as Kcruella says, with Marines as parents, the boys’ choice of services was always a “little knife through the heart“) – kept in touch wherever they each were. They both spoke the lingo now, and the bond was even tighter. It even worked out that Ebola got to visit while on TAD at Fort Collins where John and his family were stationed.

The 12th of November 2016 started off like almost every Saturday had for the past couple years. I was at work in my friend’s store downtown. FoxNews was on – we weren’t really busy yet and could get away with it. Over the top of the racks I heard “bombing” and looked up to see a newsflash about the first reports of a suicide bombing at Bagram airfield coming in.

John was at Bagram, having volunteered to go back again with his short-handed shop instead of a special duty assignment stateside.

But the reports were sketchy and there were none about casualties, so I said a quick prayer and kept motoring.

About 40 minutes later, my cell rang, and it was Kcruella. She was a little rattled because she couldn’t get ahold of John, as moms want to do. I told her not to worry, that I’d get ahold of Ebola, since I knew he was at work (stationed on Guam at the time) and see what he could find out for us. I called her back about a half an hour later to tell her he’d said that made perfect sense. They’d naturally shut all communications down after an incident like that for security reasons. Ebola said to give it time.

I finished up my day and went home.

The landline at the house rang and when I answered a woman was screaming so that I had to say, “I’m sorry. I don’t understand you, ma’am.”

“It was John! John’s gone! Oh, my God, what am I going to do without my baby?!”

My heart froze. I’ve never heard such pain. I’ve never felt such pain. And I could do nothing to help my best friend in the world. My sister.

major dad looked at me and said “What’s the matter?” and all I could say was,

“It was John. John is gone.”

I had to tell Ebola by Facebook messenger his little brother was gone. I couldn’t even comfort my son.

We buried John at Arlington that December on what had to be the coldest day in recent memory. Howling, freezing winds didn’t stop the flood of Marine Corps friends from decades ago nor John’s childhood buddies from coming to D.C. to support and show their love. Ebola, just off the flight from Guam, so handsome and heartbroken – in his dress blues for his little brother.

Even as we age-old friends and family walked with Kcruella and the horse-drawn caisson carrying our boy, Marines came over the gently undulating rows of graves to join the procession – long-ago friends arriving who knew what this moment and this sacrifice meant.

They came to honor John.

They came to grieve.

I will leave you with Ebola’s eulogy, written for his little brother the night we learned of his loss.

I was raised the sole child of two Marines in Southern California; my friends and my family are their friends/coworkers and children from while my parents were stationed there. Three of those children were my brothers, even while we’ve always referred to each other as cousins over the last thirty years. Years of playing hide and seek, riding bikes, of reiterating every line to Predator and/or Aliens as the movies played, laughing and bitching at each other, playing capture the flag, tag, finding injured animals and trying to nurse them to health, and telling bad jokes. We’ve all gone our separate ways over the years: the twins are successful in business, the other two of us entered service. All of us rarely get to see each other, even for special occasions, but it’s always the normal sh*t talking, smiles, laughter, the hate and situational discontent of youngsters. We all still talk to this day, almost thirty years later.

At 0136Z on the 12th of November, while I slept in the comfort of my home in the Pacific, the Taliban took part of my childhood. They took our brother. They took him from a loving wife, their beautiful children, from his mother and father, from an extended family, of blood and without, who loves him dearly. I’d just shot him a message ten days before, telling him happy birthday. I can’t stop reading our last email chain, filled with our normal bullsh*tting, split over days due to conflicting schedules and locations.

John: “What do you think you’re doing?”

Me: “I assume making huge mistakes and blaming other people. How’s life cuz?”

John: “Life is good. Probably not as pleasant as Guam, but the ol’ Stan has its perks. You can buy a magic carpet over here but it won’t fly. It will make around $1500 disappear from your wallet. I just got a box from your mom and dad loaded with cookies. How much longer is your tour over there?”

Me: “Probably extending until Oct. Waiting to see if my SERE instructor or HUMINT packages get accepted. If they do, the AF retains me, if not I get out and go back to contracting. How in the f*ck do camel rugs run 1500? What a racket. lol”

John: “So you’re staying in Guam until October or are you getting out then? Those rugs are expensive but about 1/4 the cost they are in the states for a handmade Kashmir Persian rug. Smoother and softer than a babys’ ass. They’ve got all kinds of crap out here you can get custom made. I’m thinking about getting a new MOS myself but I’ve got to wait until I get back and find out where the Army is sending me next.”

The last words between John and I are shooting the sh*t about a f*cking rug. To be honest, I wouldn’t have it any other way: it was us, as we’ve always been. We’re both family and we know it, it never required quaint expressions or platitudes of familial bullsh*t. I chuckle thinking about it, things never changed in all those years, even though we’re both vastly different individuals from who we were in our youth. I still remember trying to explain to him as kids that his wearing his LA gear shoes lit up and gave away our position during capture the flag. His talking me into telling a dirty joke, memorizing it the first time through, smiling and running to rat me out to Pop.

I can’t do sh*t but sit here, hate that I can’t kill every one of these goat f*cking sh*t shamans, and wait for a time where I can do something besides tell our families I love them. When I came into the Air Force, my highest honor, to this day, was escorting my flight commander, Nathan Nylander’s family. The distinct, burning memory I have of that is standing at attention on the flight line as his body was brought off the aircraft, and having his young children begin to cry, not a stones toss from me, as the realization set in that it was really happening. It f*cking destroyed me. That pain, though painfully memorable, was momentary. It was the singular hardest thing I’ve ever had to do, until now. I know that is coming for my family and the absolute pain and hatred it inspires in me is indescribable. I want to strike out, to defend something that has already passed defending. There is nothing but the most tenuous vapors the wind to strike at. My hatred accomplishes nothing, which only makes me hate all the more deeply. I am sitting at the squadron right now as I write this, a non-commissioned officer in the strongest military on the planet, thousands of miles from our families, on a beautiful island filled with wonderful people that can’t drive to save their lives… and //I can’t f*cking do anything.// Now, I’ve typed a small book and said nothing I wanted to say by it.

I’ll close with what John already knew: I love him like a brother, and I wish all our/my friends had had the opportunity to get to know the f*cking badass he grew into. I have no hesitation in saying he grew into a better man than I did and that will live on through his children.

Oh, we miss you, John. Every single day.

Please have a grateful Memorial Day.

Semper Fi.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member