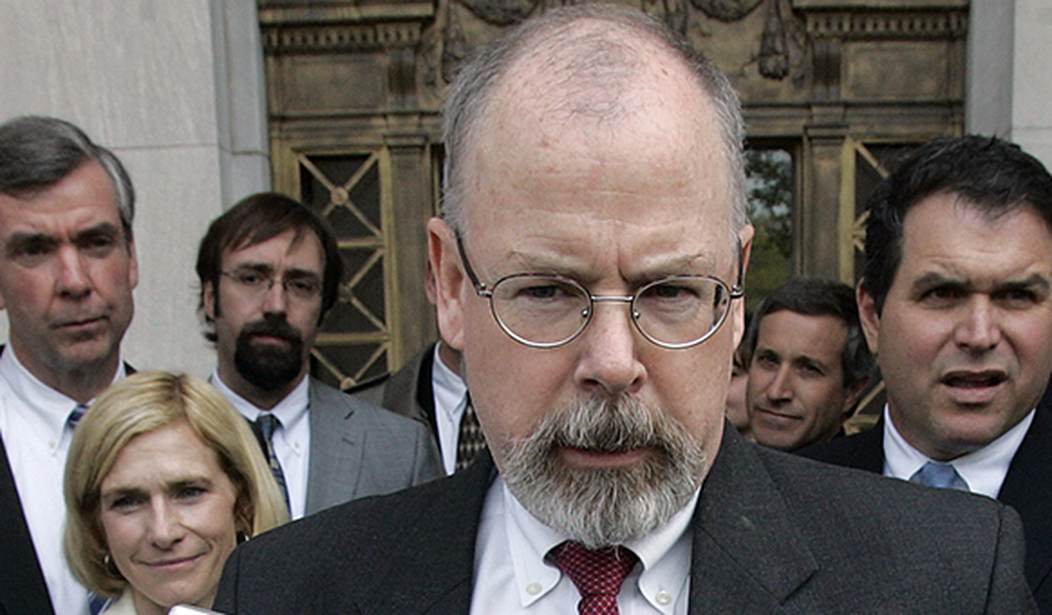

Last September John Durham’s investigation indicted Michael Sussmann for (allegedly) lying to the FBI. The gist of the case against Sussmann was that prior to the 2016 election he’d taken claims that the Trump campaign was secretly communicating with Russia’s Alfa Bank to James A. Baker, general counsel at the FBI. When asked by the FBI if he was there on behalf of a client, Sussmann said no. He was essentially claiming he was just there as a concerned citizen. But that wasn’t true, according to Durham. Sussmann was in fact working for the Clinton campaign and even subsequently billed the campaign for the meeting with the FBI.

In December, the NY Times reported on some additional evidence which seemed to back up Durham’s case. Though the meeting between Sussmann and Baker wasn’t recorded, two different FBI agents whom Baker spoke to about the meeting both made notes that Sussmann had claimed he had no client.

One piece of newly disclosed evidence, described in a filing by Mr. Durham’s team on Tuesday evening, consists of handwritten notes by an F.B.I. lawyer to whom Mr. Baker spoke about the meeting that day. The Durham filing quoted the notes as saying “no specific client.”

That evidence is similar to another set of handwritten notes previously cited in the indictment by another F.B.I. official who also spoke to Mr. Baker after the meeting.

Today, Fox News reports that Sussmann has filed a motion to have the case against him dismissed claiming “extraordinary prosecutorial overreach.” Sussmann isn’t exactly claiming that he didn’t lie to the FBI, he’s claiming that even if he did the lie shouldn’t be prosecuted.

“It has long been a crime to make a false statement to the government. But the law criminalizes only false statements that are material—false statements that matter because they can actually affect a specific decision of the government,” the lawyers wrote, adding that, by contrast, false statements “about ancillary matters” are “immaterial and cannot give rise to criminal liability.”

“Accordingly, where individuals have been prosecuted for providing tips to government investigators, they have historically been charged with making a false statement only where the tip itself was alleged to be false, because that is the only statement that could affect the specific decision to commence an investigation,” the lawyers wrote. “Indeed, the defense is aware of no case in which an individual has provided a tip to the government and has been charged with making any false statement other than providing a false tip. But that is exactly what has happened here.”…

“He met with the FBI, in other words, to provide a tip,” Sussmann’s lawyers wrote. “There is no allegation in the indictment that the tip he provided was false. And there is no allegation that he believed the tip he provided was false. Rather, Mr. Sussmann has been charged with making a false statement about an entirely ancillary matter—about who his client may have been when he met with the FBI—which is a fact that even the Special Counsel’s own Indictment fails to allege had any effect on the FBI’s decision to open an investigation.”

To be clear, the filing doesn’t admit Sussmann lied to the FBI. His attorneys are still claiming that he did not lie about his client. But the focus of the filing is that even if he had the lie wasn’t material.

That said I don’t think it’s hard to see what is going on here. There’s evidence that Sussmann did lie, but he’s now arguing such a lie shouldn’t be prosecuted anyway because it wasn’t significant to whether or not the FBI opened an investigation in the case.

Of course there’s a reason why Baker asked if Sussmann had a client and why the FBI agents he spoke with subsequently made special note of the fact that Sussmann claimed not to have one. It was relevant to how seriously they should take his tip. Indeed, the Durham indictment said as much. But Sussmann’s motion says that’s not enough.

[Durham’s indictment] alleges that Mr. Sussmann’s purported false statement was material because it was “relevant” to the FBI whether he was providing the information “as an ordinary citizen” or whether he was doing so “as a paid advocate for clients with a political or business agenda.” Id. ¶ 32. The Paragraph goes on to explain the reason that this would have been “relevant” is because it “might have” led the FBI General Counsel to ask about the identity of Mr. Sussmann’s clients; the FBI “might have” taken “additional or more incremental steps before opening and/or closing an investigation”; the FBI “might have allocated its resources differently” and “uncovered more complete information.” Id. (emphasis added). Again, nowhere in the Indictment is there an allegation that the information Mr. Sussmann provided was false. Nowhere is there an allegation that Mr. Sussmann knew—or should have known—that the information was false. And nowhere is there an allegation that the FBI would not have opened an investigation absent Mr. Sussmann’s purported false statement. The closest the Indictment comes is the suggestion that Mr. Sussmann’s supposed client relationships were “relevant” because they “might have” led the FBI to take “additional or incremental steps.” But the law in this Circuit is clear that relevance is not enough to establish materiality because “[a] statement may be relevant but not material.” See Weinstock, 231 F.2d at 701 (“To be ‘relevant’ means to relate to the issue. To be ‘material’ means to have probative weight, i.e., reasonably likely to influence the tribunal in making a determination required to be made.”); see also, e.g., Litvak, 808 F.3d at 174 (stating that materiality was not proven where the government only “established that [defendant’s] misstatements may have been relevant to the” government decisionmaker). And the operative governmental decision here is not how the FBI would have gone about opening an investigation, but whether the FBI would have opened that investigation…

At the end of the day, Hillary Clinton herself could have publicly handed over the Russian Bank-1 Information and the FBI would still have investigated it. And if Mr. Sussmann had not met with Mr. Baker and Newspaper-1 published its article as anticipated, see Indictment ¶ 27(e), the FBI surely would have initiated its investigation then as well. Thus, Mr. Sussmann’s purported statement about his clients was utterly immaterial to the decision of whether to investigate the Russian Bank-1 Information because it is precisely the kind of “ancillary, non-determinative fact,” Naserkhaki, 722 F. Supp. at 248—or “trifling collateral circumstance,” Kungys, 485 U.S. at 769—that has never given rise to criminal liability.

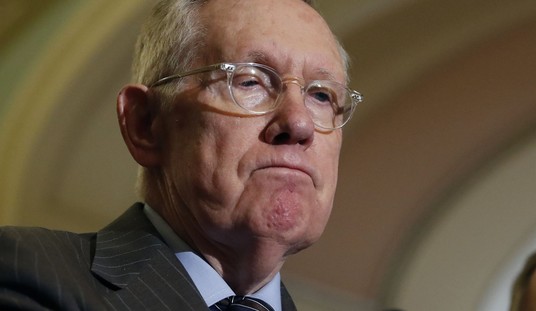

Hillary Clinton herself did in fact promote this scam on Twitter:

Computer scientists have apparently uncovered a covert server linking the Trump Organization to a Russian-based bank. pic.twitter.com/8f8n9xMzUU

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) November 1, 2016

We’re getting is an inside look at how things operate within Clinton World. Sussmann’s tip looks like a carefully crafted October surprise, one which was probably meant to generate negative headlines prior to the election. The Alfa Bank story was eventually determined by the FBI to be junk and there’s at least some evidence Sussmann may have lied about who he was working for when he brought those claims to the FBI. On the other hand, he has argued that basically everyone in Washington knows he’s a lawyer who works for Democrats. His partisan leanings weren’t a secret.

Bottom line: All of this looks extremely shady, not unlike Clinton’s own decision to run a private email server in the basement of her home. But as always, Clinton World doesn’t care if something is shady and dishonest it only cares if it’s illegal. That’s the line being drawn here. I guess we’ll have to wait and see what Durham’s team has to say in response to this motion.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member