This morning’s Gospel reading is Luke 20:27–38:

Some Sadducees, those who deny that there is a resurrection, came forward and put this question to Jesus, saying, “Teacher, Moses wrote for us, If someone’s brother dies leaving a wife but no child, his brother must take the wife and raise up descendants for his brother. Now there were seven brothers; the first married a woman but died childless. Then the second and the third married her, and likewise all the seven died childless. Finally the woman also died. Now at the resurrection whose wife will that woman be? For all seven had been married to her.”

Jesus said to them, “The children of this age marry and remarry; but those who are deemed worthy to attain to the coming age and to the resurrection of the dead neither marry nor are given in marriage. They can no longer die, for they are like angels; and they are the children of God because they are the ones who will rise. That the dead will rise even Moses made known in the passage about the bush, when he called out ‘Lord,’ the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob; and he is not God of the dead, but of the living, for to him all are alive.”

Sometimes, it’s tough to tell the players without a scorecard, and this matters today understand the meaning behind the arguments in this Gospel reading. Luke notes explicitly that the Sadducees — one of three groups in Judean leadership challenging Jesus in His ministry — did not believe in resurrection, but there is more to this confrontation than just that one point.

The Sadducees make only a handful of appearances in the Gospels (16 mentions), but not because they were unimportant. Jesus contends more often with the Pharisees (107 mentions) and scribes (dozens) more often in the Gospels; Jesus also calls them out by name, such as in Mark 12 and the Woes of Matthew 23. The scribes were the lawyers and learned class, while the Pharisees overlapped them to some extent as interpreters and enforcers of the Law. Needless to say, the Pharisees in the Gospels do not come across well; they were part of the Judean authorities that Jesus challenged for leading His flock astray. However, the Pharisees would eventually establish the basis for rabbinical Judaism that exists to this day, allowing its survival after the destruction of the second Temple. Theirs is a remarkable story, which we don’t appreciate often enough.

But who were the Sadducees, what was their distinction from the Pharisees, and why do we read about their challenge to Jesus? The Sadducees were the aristocratic, upper-class Judean clique who held the real power at the time of Jesus’ ministry, at least among the Judeans. They controlled the priesthood and with it the real temple power through the Sanhedrin. (Presumably, the oft-repeated term “chief priests” would likely refer to the Sadducees, at least in part.) Unlike the Pharisees, the Sadducees rejected oral tradition and demanded a kind of sola scriptura reliance on the written Law and the centrality of Temple worship. More so than the Pharisees, the Sadducees represented the corrupted power structure among Judeans of the period that Jesus meant to challenge.

One other important distinction existed between the Pharisees and the Sadducees as well: the belief in an afterlife. The Pharisees believed in it and in a spiritual creation complete with angels. The Sadducees not only rejected the concept of resurrection — the bodily transformation after death — they rejected the idea of an afterlife entirely.

A priest once offered me a humorous way to recall that distinction: “The Sadducees didn’t believe in an afterlife, which made them sad, you see.” Yeah, it’s a kind of Dad joke. Or in this case, a Father joke. But it works as a mnemonic!

Anyway, the rejection of belief in an afterlife didn’t make them sad, but it did make them particularly inflexible and resistant to Jesus’ message about the nature of the Messiah and salvation. The Pharisees would have been at least more open to the concept, even if they were skeptical and outright hostile to Jesus Himself. His teachings were anathema to the Sadducees and their power, which was entirely based on material Creation and control of the Temple as the only pathway to the Lord.

That brings us to the confrontation here, in which the Sadducees intended to defeat Jesus through a reductio ad absurdum argument to discredit the notion of resurrection into Heaven. To believe that one will encounter the Lord after death at the very least diminishes the role of the Temple in life, and with it the Sadducees’ control over the ability of people to experience His presence. Jesus’ argument had to be defeated in order to protect that power, and the Sadducees figured they could discredit Jesus with some hyperbolic ridicule.

And it might have worked, except that the Sadducees’ beliefs and incentives for power blinded them to the true nature of Creation. Jesus reminds them that the Lord is the God of the living, hearkening back to Moses as the authority on which the Sadducees also relied. It is a context that the Sadducees either refused to consider or never recognized in the first place. In essence, the Sadducees make the same mistake many of us make as well — they interpret Heaven through the context of a fallen world, not of Creation as the Lord desired it to be.

The Sadducees’ basic error of seeing the written Law as the beginning and end of worship blinded them to the truth, not just of Creation but also the Law. However, the Lord gave us the Law to find Him through the chaos of the fallen world — a means, not an end.

Our first reading from 2 Maccabees 7 reflects this same point, in a passage that even reflects the Sadducees’ argument in referencing seven brothers. In the uprising against the Hellenists of that era, seven brothers rebel and remain loyal to the Law — both for love of the Lord and for the hope of living in His presence after the end of their lives. Their torturers wanted the Judeans to convert to their worldly, temporal approach to life, but the Maccabees instead led a revolt in Judea that renewed faith in the Lord and eventually brought victory over their oppressors.

Today’s reading describes how four of the seven brothers die proclaiming their coming resurrection into His presence through their obedience and martyrdom rather than surrender to their oppressors. Their mother, who watched six of her seven sons die at one point, praised God for their courage and example in a later passage:

The mother was especially admirable and worthy of honorable memory. Though she saw her seven sons perish within a single day, she bore it with good courage because of her hope in the Lord. She encouraged each of them in the language of their fathers. Filled with a noble spirit, she fired her woman’s reasoning with a man’s courage, and said to them, “I do not know how you came into being in my womb. It was not I who gave you life and breath, nor I who set in order the elements within each of you. Therefore the Creator of the world, who shaped the beginning of man and devised the origin of all things, will in his mercy give life and breath back to you again, since you now forget yourselves for the sake of his laws.”

At this point, the king also had the youngest son tortured and killed along with the mother. She too went to the Lord rather than choose material comfort — or at least life itself — which testifies to its meaning and value. It’s not that temporal life is meaningless or valueless, but that meaning and value derive from its service to the Creator whence both spring.

Furthermore, the mother’s humble declaration of the origin of her sons’ faith and courage highlight Jesus’ point. The fallen world has its own context, and the institutions for living in it serve the Lord here, including marriage and also the Temple itself. The Temple served the Lord and the people as a means of communion and atonement, but was not the Lord Himself. The Sadducees were not the first to make that mistake; Jeremiah repeatedly warned the Judeans that the Lord would not protect Jerusalem if the people kept turning away from Him, regardless of whether the Temple was there or not. The Temple was a convention established for the benefit of a faithful people, not a trap for God, just as marriage is a convention for God’s children to navigate this world.

The Sadducees could not see this because they refused to see past this world. The Pharisees could, but didn’t grasp that the Messiah would bridge all of Creation rather than come as a warlord on Earth. Both suffered from blindness of sorts, incentivized by their own designs but mainly by lacking the context necessary to see the truth — even when Jesus presented it to them.

All of this should prompt us to reflect on our own blind spots, our own misunderstandings of the Gospel message. How often do we see mercy and justice, for instance, through the concepts of human institutions in this life? How often do we rely on written laws and stripped context from scripture to make judgments? Do we have faith in the Lord that His living presence will provide us eternal life on His terms rather than ours, or do we already have our own expectations and demands on Heaven based on a complete lack of experience as to what it will mean?

To miss those blind spots, even if we can’t correct them fully, is to risk being led astray into inflexible and incorrect positions. That closes us off from the truth, just as it did with the Sadducees and Pharisees, and leaves us open to destruction rather than salvation. And that will most definitely make you sad, you see, rather than joyful in His eternal presence.

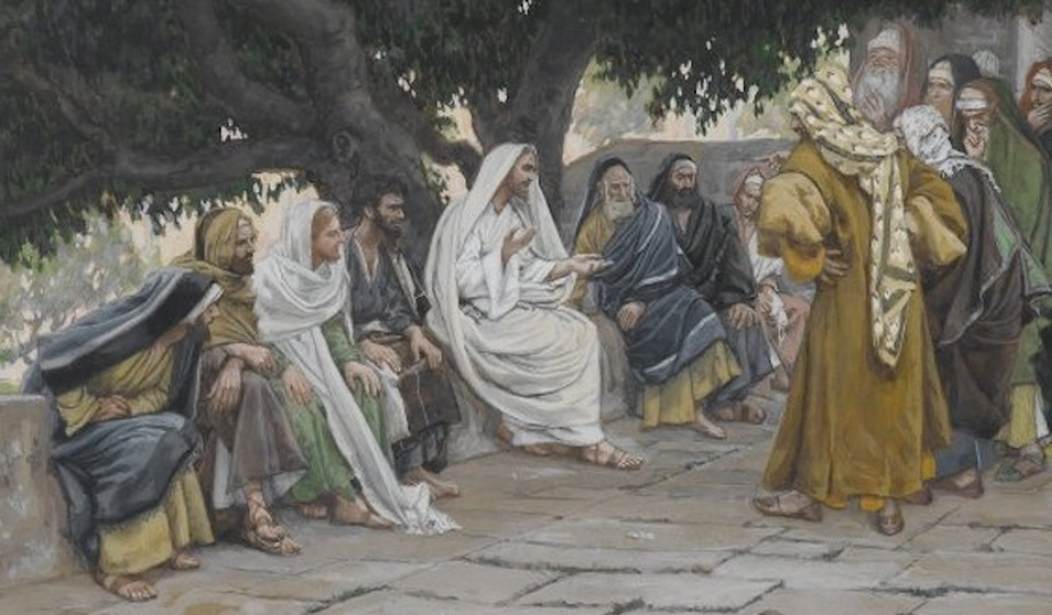

The front-page image is a detail from “The Pharisees and Sadducees Come to Tempt Jesus” by James Tissot, c. 1886-94. On display at the Brooklyn Museum. Via Wikimedia Commons.

“Sunday Reflection” is a regular feature, looking at the specific readings used in today’s Mass in Catholic parishes around the world. The reflection represents only my own point of view, intended to help prepare myself for the Lord’s day and perhaps spark a meaningful discussion. Previous Sunday Reflections from the main page can be found here.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member