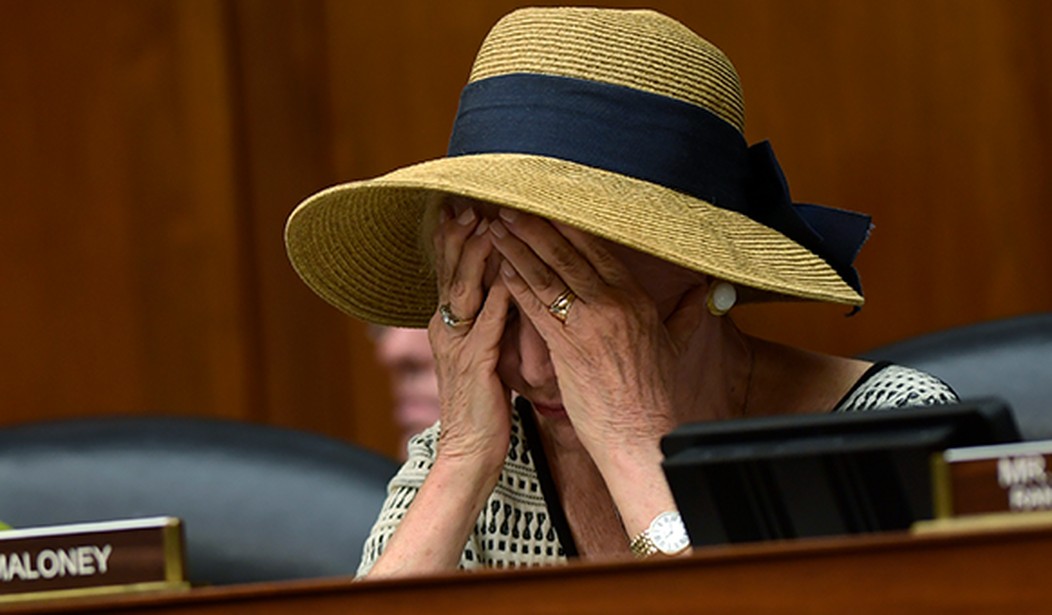

Can the administrator of the National Archives simply declare the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) ratified and part of the US Constitution? That’s what House Democrat Carolyn Maloney (D-NY) and several ERA backers now claim, a position also embraced by Joe Biden. Maloney claims that NARA administrator David Ferriero committed to executing that plan almost a decade ago, and now wants Ferriero to make good on his promise:

“When he [David Ferriero] first became the archivist, I wrote to him about the ERA and that it was his job to certify it. He wrote me back — I have got the letter — saying he supports the ERA and that he would do it.” …

“He says he believes in the ERA. Well, if you believe in it, just certify it. He’s the one holding it back,” Maloney said at a news conference sponsored by the ERA Coalition. “And it’s a technicality. Equality is not a technicality. Equality is a right. We have met every single requirement that was put forward. There were only two in the Constitution. One was that you had to have two-thirds of Congress; we had more than two-thirds of Congress when we passed it. And that 38 states needed to ratify it. We’ve done that!”

Is that how constitutional amendments work? Baloney, writes Glenn Kessler, and so are Maloney’s claims about the letter from Ferriero. Not only is this nonsense, it has been repeatedly tested and has repeatedly failed in courts, all the way up to the Supreme Court.

First, Maloney’s flat-out lying about the letter, Kessler points out:

The letter referenced by Maloney — who heads the House committee that oversees NARA — indicates no support by the archivist for the ERA. … Maloney’s staff sent us a legal analysis disputing the Trump OLC opinion but, despite repeated requests, did not address why she claimed that Ferriero had written to her that he was a supporter of the ERA.

More to the point, the archivist has nothing to do with it. As Kessler points out, the vote in Congress to refer the ERA to the states had a time limit for full ratification. Courts have consistently upheld Congress’ authority to impose such a deadline. That has been a common practice for the past century, Kessler points out, and in this case was a significant bargaining point. The deadline was a crucial element in getting the necessary two-thirds vote in each chamber for the referral in the first place.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court tacitly endorsed the legality of the deadline. A case filed by Idaho challenged the legality of a three-year extension tacked on by a simple majority vote, and the extra three years got thrown out. That case went to the top court, which ended up recognizing deadlines as a cause for mootness on the issue:

The Supreme Court stayed Callister’s ruling and was prepared to review the case. But after the 1982 deadline passed without the necessary votes for ratification of the ERA, the high court then declared the case moot and ordered it dismissed. Without saying so directly, the Supreme Court appeared to accept that the deadline was valid.

There has been a considerable amount of litigation in recent years as some states continue to generate ratifications. Ferriero has requested legal opinions from the DoJ over this in both the Trump and Biden administrations, both of which have recognized the deadline. Ferriero has been sued in court, but even a judge appointed by Barack Obama has tossed out claims that the ERA has been properly ratified:

Meanwhile, U.S. District Judge Rudolph Contreras, also an Obama appointee, heard the lawsuit filed by the three late-ratification states. In 2021, he dismissed the case. Not only did the states lack standing to sue, but “even if plaintiffs had standing, Congress set deadlines for ratifying the ERA that expired long ago,” he wrote.

The Contreras opinion is interesting because he evaluated many of the arguments made by ERA supporters, such as Maloney, and found them wanting. For one, he rejected the idea that the archivist could wave a wand and declare that the ERA had passed: “The Archivist’s publication and certification of an amendment are formalities with no legal effect.”

Second, he found the ratification deadline in the ERA to be valid and that it would be “absurd” for the archivist to ignore it.

Indeed it would be, and Maloney’s not the only one indulging in absurdities. Joe Biden has repeatedly bought into the same nonsense, most recently three weeks ago:

I am calling on Congress to act immediately to pass a resolution recognizing ratification of the ERA. As the recently published Office of Legal Counsel memorandum makes clear, there is nothing standing in Congress’s way from doing so.

Nothing except the fact that it failed to get ratified within the deadline set by Congress, which expired decades ago. Maloney and the DoJ can appeal Contreras’ ruling, but it’s not likely to get much sympathy from judges who will not only point to the original deadline as valid but wonder why it took so long for advocates to press this case. The clear answer to a failed amendment would be to try again — and if it’s as popular as Maloney and Biden claim, then ratification shouldn’t be a problem.

Kessler gives Maloney Four Pinocchios for flat-out lying about Ferriero and the status of the ERA, and Biden certainly gets his share of that same award.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member