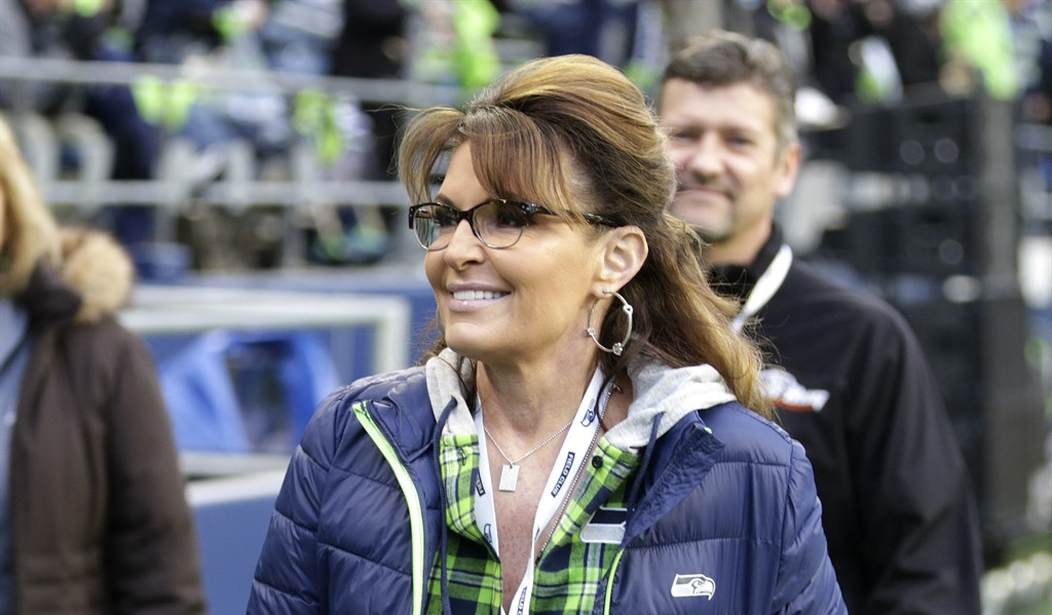

Will Sarah Palin force the New York Times to write a big check for defamation, or will the ghosts of Sullivan save the newspaper again? Palin’s long-awaited lawsuit will open today in federal court over an editorial that initially blamed Palin for the 2011 shooting that killed several people and gravely wounded then-Rep. Gabrielle Giffords. Palin filed the lawsuit after the June 2017 house editorial that insisted that “the link to political incitement was clear.”

The link in fact didn’t exist at all, a fact that had been known to everyone since shortly after the shooting. The shooter turned out to be a dangerous, mentally ill person who had no connection to politics. The New York Times corrected the editorial, but Palin had had enough of these claims. And now the Times will have to disclose exactly how the supposedly leading US newspaper didn’t know what actually transpired six years later.

Good luck with that, but Palin will need some luck as well. Reuters offers a highly skeptical look at Palin’s chances today, noting the Sullivan standard for “actual malice”:

It said “the link to political incitement was clear” in the 2011 shooting, which followed the circulation by Palin’s political action committee (PAC) of a map putting 20 Democrats including Giffords under “stylized cross hairs.”

The Times quickly corrected the editorial to disclaim any connection between political rhetoric and the 2011 shooting, and Bennet has said he did not intend to blame Palin.

But Palin said the disputed material fit Bennet’s “preconceived narrative,” and that he was experienced enough to know what his words meant. …

To prevail, Palin must show by clear and convincing evidence that “actual malice” underlay the editorial. The U.S. Supreme Court adopted the actual malice standard in 1964 for public officials, making it difficult for them to win libel lawsuits.

“The key will be showing how the editorial came together,” said Timothy Zick, a professor and First Amendment specialist at William & Mary Law School. “Essentially, did the Times do its homework before publishing?”

Are we kidding? Six years after the Tucson shooting, it would have been impossible not to learn that Jared Loughner was a paranoid schizophrenic with a fixation on Giffords and a social-media track record of rants about “waking dreams” and delusions. One would expect a news organization to do some basic research on the subject before reverting to a long-debunked hypothesis that Loughner was motivated or indeed had any knowledge of Palin’s campaign materials. Clearly, the Times didn’t do its homework, and one has to figure that Palin’s determination to bring this to trial is motivated by the prospect of depantsing the Gray Lady and Bennett in public.

NPR’s David Folkenflik is more honest in his appraisal of the case, but also offers a cautionary note:

The case pits First Amendment protections for robust free speech against the right of someone not to be defamed, i.e. not to have damaging and untrue claims made publicly against her, even if she’s a prominent public figure. It is also likely to shine an unwanted light into the behavior of the nation’s leading newspaper when it’s under deadline pressure.

“It’s going to be ugly,” says Lucy Dalglish, a First Amendment attorney who is dean of the University of Maryland Merrill College of Journalism. If you’re a news outlet, Dalglish says, “you really never want a libel case to go to trial. It’s hard to win. It can be done, but they’re hard to win.”

There is no argument or ambiguity here about the facts: What the Times originally published was wrong.

And Bennett’s deposition might have already given Palin a head start on actual malice:

Editorial writer Elizabeth Williamson drafted the piece the day of another mass shooting, this time at a congressional baseball practice outside Washington, D.C. A man who was a supporter of liberal causes seriously wounded U.S. Rep. Steve Scalise, a top Republican from Louisiana, and injured five others.

Williamson’s boss, then-Times editorial page editor James Bennet, sought a more sweeping editorial, one that argued for greater gun control laws and against the use of heated political rhetoric and incitement, as he explained in a deposition later on.

So Bennet added a passage to the editorial saying that “the link to political incitement was clear” between Palin’s ads and the shooting in Tucson, Ariz. In fact, an ABC News story that the online version of the Times editorial linked to stated there was no proof that the gunman had seen the material from Palin’s political action committee.

Additionally, the editorial mischaracterized the Palin ad. The graphic showed crosshairs targeting 20 congressional districts, represented by Democrats, including Giffords’ in Arizona, on a map of the U.S. But it did not place crosshairs over images of the lawmakers themselves, as the Times originally suggested.

Again, let’s not forget that this was six years after the Tucson shooting. Those are facts that one would expect a news organization to get correct by that time. And actually, they had, as Folkenflik notes: their news division had previously debunked the Palin-ad hypothesis of the Tucson shooting, as had a number of other media outlets. What’s more, it is clear from Bennett’s testimony that he wanted to water down the clearly-political shooting of the Republican congressmen (by a radical supporter of Bernie Sanders) by ginning up a political motive for the 2011 shooting to get a pox-on-both-houses take.

That blew up in their faces. The editorial produced an immediate wave of criticism that pushed the Times to correct it by the next morning and apologize to readers … but not to Palin. Palin filed the lawsuit, and here we are.

Of course, Palin clearly qualifies as a “public person” for the purposes of Sullivan, which means she has a higher bar to meet for defamation. “Actual malice” has a somewhat different legal meaning than it does in conversational English:

Specifically, actual malice is the legal threshold and burden of proof a public defamation plaintiff must prove in order to recover damages, while private persons and plaintiffs need only prove a defendant acted with ‘ordinary negligence’.

Constitutional malice differs slightly from common law malice, as constitutional malice emphasizes two fundamental components; knowledge of the statement’s falsity or reckless disregard for the truth, while common law malice emphasizes the ideas of “ill will” and “spite” or the plaintiff’s feelings towards the plaintiff.

In this case, though, the underlying facts appear to make the argument for a successful defamation case. Six years after the fact, the Times’ editors revived a claim about the Tucson shooting that its own reporters debunked to score political points against Palin, in large part to deflect from the obvious motive for the shooting of the Republicans at the congressional baseball game. It’s tough to predict what any jury will do, but it seems unlikely that a jury would let “actual malice” get in the way of a judgment if they’re inclined to find against the NYT.

And even if they do, it might end up coming back. Both Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas recently called for a reconsideration of Sullivan, arguing that it went too far in protecting obviously defamatory speech. If Palin has to push this on appeal to the Supreme Court, she may end up demolishing Sullivan and getting a second bite at the Big Apple newspaper. One has to wonder why the NYT didn’t settle this case before today and offer a big apology along with a big paycheck.

Update: I missed it earlier, but the start of the trial has been postponed due to the former governor’s acute case of COVID-19.