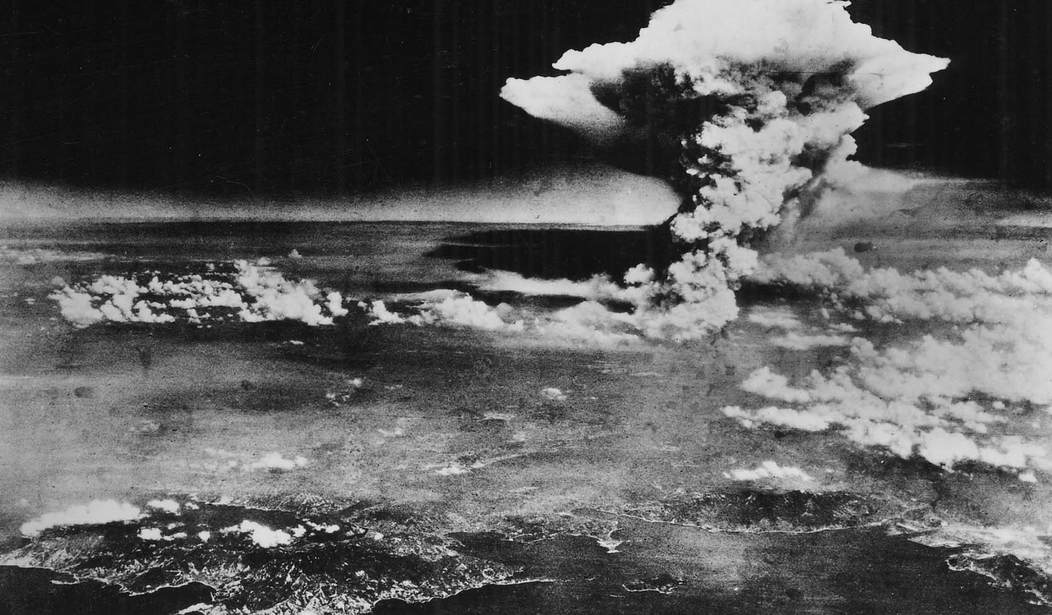

Eighty years ago today, the United States ushered the Atomic Age into being with a single air strike on the city of Hiroshima. Three days later, the US dropped another atomic bomb on the city of Nagasaki. And ever since, the global and media establishment has worked hard to apply "perfect retrospection" to those decisions in order to paint Harry Truman as the villain of August 1945, and the US as war criminals for a war fought on Japan's terms.

We can expect the 80th anniversary of these events to provide more historical revisionism and ex post facto judgments on these two bombings. In fact, I expect that to such a degree that I won't even bother linking to such arguments, as they have become the Received Wisdom among the cognoscenti for decades. We saw that plainly enough in the Christopher Nolan film Oppenheimer two years ago, which promoted the idea of Japanese victimization at the hands of a cruel Truman and his bloodthirstiness.

Unfortunately for the cognoscenti, the evidence to the contrary is both abundant and accessible. Historian Richard Frank tackled all of the material from government records, both from the US and the Japanese Empire, in his comprehensive and essential book Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. I wrote about this two years ago shortly after writing about Oppenheimer, to which I'll return in a moment.

However, Frank himself returns today at National Review to remind everyone that the historical revisionism around Hiroshima and Nagasaki is, in fact, nonsense. Much of this is behind the paywall, and a subscription is worth the price to access this brief condensation of Downfall. (It's not easy to find the book, as I detailed two years ago.) Frank blasts the "moral indictment of the bombings" preferred by the global establishment (although Frank also rejects the term "revisionism" as well). Frank covers the broad strokes of all the evidence in this essay, but we should especially focus on the moral inversion that has taken place in the past 80 years about who precisely got "victimized":

Most fundamentally, this moral indictment works from a grossly upside-down portrait of the number and identity of the war’s victims. Further, its factual premises were undermined with the release of extensive new evidence from the 1990s, notably in the U.S. and Japan.

The first basic point is that this war was not merely the “Pacific War.” That narrow lens treats events as though they were bound between December 1941 and August 1945. It foregrounds the conflict between the United States and Japan across the Pacific. It recognizes only a handful of additional participants: the Philippines, Australia, Pacific Islanders, and New Zealanders. The actual conflict properly identified is the Asia-Pacific War. It commenced with Japan’s assault on China in July 1937 and only ended officially 97 months later — although fighting continued “postwar” in Asia for years. Japan enormously expanded the war starting in December 1941 to reach India on the west and pierce far into the Pacific Ocean on the east.

The Asia-Pacific War killed 25 million human beings, by conservative count. Of these, about 6 million were military personnel, including about 3 million Chinese and 2 million Japanese. There were 19 million dead civilians — or three dead civilians for every combatant death. A reasonable range of European war casualties reaches the vicinity of 37–48 million, but the ratio of civilians to combatants does not rise above two to one.

Of the Asia-Pacific War civilian dead, 1–1.2 million were Japanese, including about 210,000 immediate and latent deaths at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This leaves about 18 million dead civilians who were not Japanese. Extremely few of these were white. The 18 million comprises 12 million Chinese, 2.7 million Indonesians, 1 million Vietnamese, and about 2.3 million spread among other peoples of Asia and the Pacific. Framed another way, Japanese civilian deaths form about 6 percent of all civilian deaths, and atomic-bombing-related deaths make up less than 2 percent of all civilian deaths.

That's as far as I'll go in excerpting Frank's essay. If you cannot find a copy of Downfall, I would highly recommend tossing a few dollars into NRO's coffers to read it all.

Shortly after reading Downfall, I wrote a review/analysis of Frank's comprehensive research and gripping text. That I can repost at length, and today is a very good time to revisit it:

The book is very detailed but still a compelling read and impossible to sum up in an article here. In fact, it’s so complicated that Frank ends up using the last two chapters, especially the last one, to deconstruct and rebut the revisionism that had gripped this question in the fifty-four years that passed between the war and the publication of his book.

Nevertheless, let’s roll through a few of the important points, while still recommending that readers should really find the book themselves for the underlying details.

- The question of civilian deaths — By this point of the war, American bombing doctrine had adopted city-destroying patterns of incendiary bombing, resulting in tens of thousands of casualties in each instance. Japan had adopted a somewhat decentralized war-industry model in which workers fabricated key components from their homes. The bomb damage assessment photos revealed these workshops early, and the need to aggressively end Japan’s war production resulted in the shift of tactics. BDAs eventually used estimates of the percentage of urban destruction as a performance metric, under General Curtis LeMay. The two atomic bombs achieved similar results with one drop rather than hundreds of sorties, and from high altitude with more safety to the pilots.

- Willingness to surrender and the status of the Emperor — Many revisionists blame the US demand for unconditional surrender for the reluctance of Japan to end the war. Had we just let them know that we would allow the Emperor to remain in place, the argument goes, Japan would have surrendered before Hiroshima and certainly before Nagasaki. This is nonsense, which Frank shows in multiple ways. In the first place, the Potsdam Declaration strongly hinted that the Japanese people could choose to keep its emperor, but that wasn’t enough for Hirohito or his war cabinet. The imperial regime spent July and August trying to offer concessions to the Soviet Union to broker an end under the following conditions: no occupation of Japan, no war crimes tribunal by the allies, and the “independence” of all Japanese conquests that would force withdrawal by American forces in the region. The formulation that revisionists claim as a solution – surrender while leaving the emperor in place — was explicitly rejected several times in communications with their diplomat in Moscow. He repeatedly warned Tokyo that they had no clue about the realities of their situation, even after the the bombs had dropped.

- Imminent starvation — The Allies had cut off Japan’s supply lines by the summer of 1945. An invasion would not only produce massive casualties for both sides — Japan had a 1:1 ratio against the planned US invasion of Kyushu — but any prolonged conflict could produce millions of deaths in rapid order as food supplies ran out. Even with the surrender and occupation, the US only narrowly avoided a massive famine on an unimaginable scale, as Frank details. The only way that was avoided was by the unconditional surrender. (By the way, the only conventional alternative to invasion — a blockade-bombardment strategy that Nimitz was starting to favor — would likely have made a famine even worse.)

These are just a few of the many arguments Frank puts forward in his book to answer revisionist theorizing about the non-atomic counterfactual. But to this, we must add the context of Japan’s conduct in the war, and their fanatical adherence to bushido code to justify it. No less than Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan was predicated on their belief in absolute racial/spiritual superiority. On that basis, their soldiers had brutalized China, Korea, the Philippines, Manchuria, and everywhere else they conquered. Their fanatical leadership believed in preordained ‘supremacist’ victory so thoroughly that they wanted to lure the US into an invasion of Kyushu, where they believed we would get so badly bloodied that we would thereafter leave them in place. That was the entire point of Ketsu-Go, their strategy for the invasion — to use Japanese civilians and nearly 600,000 soldiers in Japan as fodder for a battle that would have made Okinawa look like a day in the park and force the Americans to negotiate on Japan’s terms rather than ours.

The only way to break that spell was to demonstrate an ability to destroy Japan entirely without an invasion. And even with the atomic bombs, the imperial army nearly conducted a coup in order to keep fighting, which Hirohito only narrowly defeated with his radio address to the nation. It took nearly a week after Nagasaki for Japan to surrender for a reason, after all — and that surrender was necessary to ensure an end to fighting in other theaters, especially in China.

I'd offer a summation at this point to add to the devastating evidence that Frank provides. Instead, I will add in a summation from my friend Bill Whittle (via Power Line), whose video I missed in 2023 but should definitely be included today. Bill makes a powerful closing argument to the revisionists and morally inverted. Between Richard Frank and Bill, this argument should be over. It never will be, though, and so we should not shy away from restating these arguments at every occasion necessary.

Update: Ten years ago, my friend Allan Bourdius wrote an excellent argument on the 70th anniversary, right here for us. Be sure to read that as well.

Editor’s Note: Every single day, here at Hot Air, we will stand up and FIGHT, FIGHT, FIGHT against the radical left, Academia, the global elite, and the Protection Racket Media to deliver the conservative reporting our readers deserve.

Help us continue to tell the truth about America, its history, its successes, and our grand experiment in self-governance through constitutional democracy. Join Hot Air VIP and use promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your membership.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member