Bear in mind that this counts as only the second biggest disgrace in Joe Biden’s rush to retreat from Afghanistan. In terms of national security, however, it’s clearly the biggest failure in this catastrophe. By yanking all support for the Afghan military and ensuring the collapse of the government to the Taliban, the US has no way to prevent the radical Islamists from rebuilding the terror apparatus that struck US interests around the world, culminating in the 9/11 attacks.

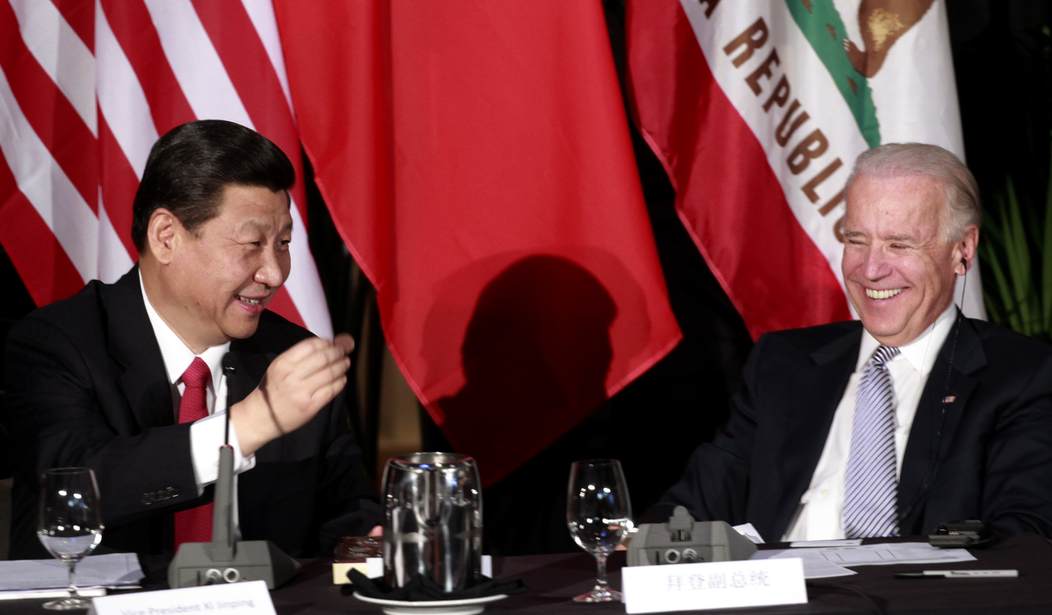

Now, all we can do is appease Xi Jinping and hope he keeps the Taliban in check, writes American Foreign Policy Council analyst Michael Sobolik. That help won’t come free — and we may already be paying the piper:

Publicly, the Biden administration is downplaying the threat to the American homeland. “They know what happened the last time they harbored a terrorist group that attacked the United States,” Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently warned. And in private, President Joe Biden is relying on a great power to keep the threat in check—but it’s not the United States. …

With America’s military footprint now virtually nonexistent, and with Washington maintaining precious little leverage over the Afghan militant movement, the White House now has no choice but to rely on the PRC to police the Taliban.

To put a finer point on it: Biden is relying on Washington’s foremost great power adversary to prevent America’s next 9/11. It is broken policy and bungled strategy, but—short of reinvading Kabul—Biden has left himself with no other options.

If that seems like a bad bet, consider the stakes. On one hand, we will likely have a network of radical Islamists operating under the Taliban’s protection with even more reason to target the US after our pell-mell retreat. On the other, we had an annual investment of around $7 billion to ensure that didn’t happen, an investment with minimal casualties (prior to the withdrawal, the last combat death occurred in February 2020). That allowed us to partner with security forces for intel on terror operations and get precise targeting, plus we kept our lines of logistical communications open.

That latter arrangement wouldn’t have been sustainable forever, of course. Nor should it have been, although it is worth pointing out that we have kept a much larger security contingent in South Korea (~25,000 troops) for almost 70 years as a tripwire against Communist aggression backed by the CCP. Technically speaking, that’s the “forever war,” as our security forces are there to enforce a cease-fire in a war that has never ended.

Still, Afghanistan’s war has essentially been a tribal civil war that has gone on for centuries rather than a strategic piece of a larger geopolitical war. At least, that was the case until the Soviet invasion in 1980, which changed all the calculations. Our involvement in the expulsion of the Soviets didn’t involve supporting al-Qaeda as some claim, but it created an environment where our allies in expelling the Russians had to play footsie with the Pashtuns who did ally with AQ and choose the Taliban as their leadership. The Pashtuns ended up winning the post-Soviet era in Afghanistan, and AQ almost immediately set up shop and began targeting the US for a series of deadly terrorist attacks.

Like it or not, the 9/11 attacks and those prior to it (embassy bombings, USS Cole) quarterbacked out of Afghanistan made the country a national-security risk for the US. Regardless of what Joe Biden says now, Afghanistan still presents a national security risk, and in fact that risk is almost certainly higher than it was twenty years ago with the Taliban’s return. That’s what makes the full pullout and abandonment of the Afghan army such a bad bet, and an unnecessary one to boot. We could have at least kept the logistical supports in place to give the security forces a chance to achieve cohesion in a post-US Afghanistan. If nothing else, it would have allowed us a much more orderly and rational withdrawal process over a period of months rather than days, one that wouldn’t have abandoned Americans to the Taliban.

Plus — and this is the real point for Xi — our position in Afghanistan gave us at least some intel access to China. Biden’s rushed abandonment of that strategic interest comes as part of a series of concessions that Biden has made to Beijing, Sobolik writes, and it’s not escaped notice in China:

It apparently hasn’t escaped Beijing’s notice that Biden has been going soft for months. In June, Biden let a handful of Chinese solar panel companies off the hook for using Uyghur slave labor, in order to protect his climate agenda. In July, the president declined to sanction the Chinese cyber espionage group Hafnium for hacking Microsoft because politicians in Brussels and London didn’t want to upset Beijing. Most recently, the administration curiously handed an economic lifeline to Huawei, a nominally private PRC tech company with an espionage and sanctions-busting rap sheet.

All of Biden’s talk about “serious competition” and “extreme competition” with Beijing is meaningless apart from an actual commitment to counter the CCP. But that’s all a moot point now. Because of Biden’s bungled exit from Kabul, America’s China policy is now subject to Beijing’s veto. In his haste to leave the graveyard of empires, Biden has killed great power competition.

Biden has forced America into retreat in a number of ways, especially on energy production, where our oil and natural gas production kept prices low and handicapped Iran and Russia. This, however, is the most direct and literal example of the Biden retreat doctrine. Not only has Biden ceded American national security to our top geopolitical foe, he’s made it all but impossible for his successors to reverse that retreat now. Our abandonment of allies and even our own countrymen to the Taliban has sent a loud signal to the rest of the world about American reliability. Don’t expect our friends to come rushing to our aid the next time around.