Profiles in Courage it ain’t, but for Democrats, it will suffice. The removal of the individual-mandate penalty — the basis for the Supreme Court’s 2012 upholding of ObamaCare — didn’t get resolved in today’s 7-2 Supreme Court dismissal of the challenge. Instead, the court ruled that the plaintiffs lacked standing to bring the case at all.

Call it the easy way out:

The Affordable Care Act on Thursday survived a third major challenge in the Supreme Court.

A seven-justice majority ruled that the plaintiffs had not suffered the sort of direct injury that gave them standing to sue.

The court did not reach the larger issues in the case: whether the bulk of the sprawling 2010 health care law, President Barack Obama’s defining domestic legacy, could stand without a provision that initially required most Americans to obtain insurance or pay a penalty.

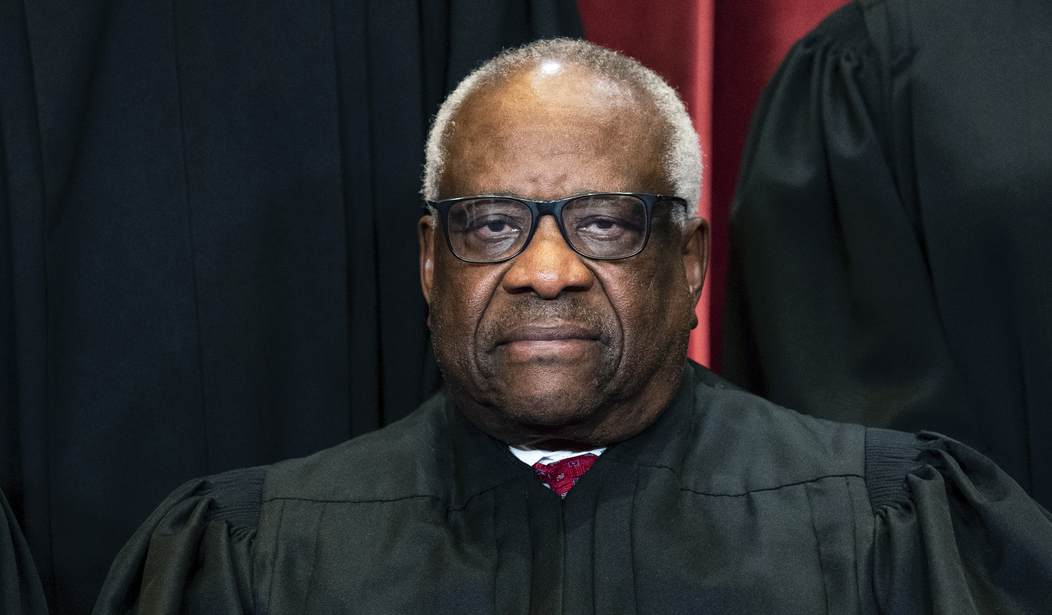

And that should be that. Not only did this conservative court dismiss the case, two of its most notable conservatives joined the majority in the decision — Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett, as well as Brett Kavanaugh for good measure. They voted with the majority in ruling that the Republican governors and the former Trump administration officials in the plaintiff position failed to show any material harm as a result of canceling the individual mandate:

(1) The state plaintiffs allege indirect injury in the form of increased costs to run state-operated medical insurance programs. They say the minimum essential coverage provision has caused more state residents to enroll in the programs. The States, like the individual plaintiffs, have failed to show how that alleged harm is traceable to the Government’s actual or possible action in enforcing §5000A(a), so they lack Article III standing as a matter of law. But the States have also not shown that the challenged minimum essential coverage provision, without any prospect of penalty, will injure them by leading more individuals to enroll in these programs. Where a standing theory rests on speculation about the decision of an independent third party (here an individual’s decision to enroll in a program like Medicaid), the plaintiff must show at the least “that third parties will likely react in predictable ways.” Department of Commerce v. New York, 588 U. S. ___, ___. Neither logic nor evidence suggests that an unenforceable mandate will cause state residents to enroll in valuable benefits programs that they would otherwise forgo. It would require far stronger evidence than the States have offered here to support their counterintuitive theory of standing, which rests on a “highly attenuated chain of possibilities.” Clapper v. Amnesty Int’l USA, 568 U. S. 398, 410–411. Pp. 11–14.

(2) The state plaintiffs also claim a direct injury resulting from a variety of increased administrative and related expenses allegedly required by §5000A(a)’s minimum essential coverage provision. But other provisions of the Act, not the minimum essential coverage provision, impose these requirements. These provisions are enforced without reference to §5000A(a). See 26 U. S. C. §§6055, 6056. A conclusion that the minimum essential coverage requirement is unconstitutional would not show that enforcement of these other provisions violates the Constitution. The other asserted pocketbook injuries related to the Act are similarly the result of enforcement of provisions of the Act that operate independently of §5000A(a). No one claims these other provisions violate the Constitution. The Government’s conduct in question is therefore not “fairly traceable” to enforcement of the “allegedly unlawful” provision of which the plaintiffs complain—§5000A(a). Allen, 468 U. S., at 751. Pp. 14–16.

Thomas’ concurring argument laments that “this Court has gone to great lengths to rescue the Act from its own text.” He also takes a swipe at the defendants, noting that they first represented the individual mandate penalty as a “linchpin” of ObamaCare, and now claim it was “a throwaway sentence.” Even with all that, Thomas writes, this new challenge is especially weak sauce:

But, whatever the Act’s dubious history in this Court, we must assess the current suit on its own terms. And, here, there is a fundamental problem with the arguments advanced by the plaintiffs in attacking the Act—they have not identified any unlawful action that has injured them. Ante, at 5, 11, 14–16. Today’s result is thus not the consequence of the Court once again rescuing the Act, but rather of us adjudicating the particular claims the plaintiffs chose to bring. …

As the majority explains in detail, the individual plaintiffs allege only harm caused by the bare existence of an unlawful statute that does not impose any obligations or consequences. Ante, at 5–10. That is not enough. The state plaintiffs’ arguments fail for similar reasons. Although they claim harms flowing from enforcement of certain parts of the Act, they attack only the lawfulness of a different provision. None of these theories trace a clear connection between an injury and unlawful conduct.

Justice Samuel Alito opposed this decision by focusing on the alleged inseverability of the mandate provision to the rest of the bill. Thomas allows that this is an interesting point, but the plaintiffs never bothered to raise it in the original challenge:

I do not think we should address this standing-through-inseverability argument for several reasons. First, the plaintiffs did not raise it below, and the lower courts did not address it in any detail. 945 F. 3d 355, 386, n. 29 (CA5 2019). That omission is reason enough not to address this theory because “‘we are a court of review, not of first view.’” Brownback v. King, 592 U. S. ___, ___, n. 4 (2021) (slip op., at 5, n. 4). Second, the state plaintiffs did not raise this theory in their opening brief before this Court, see Brief for Respondent/Cross-Petitioner States 18–30,1 and they did not even clearly raise it in reply.2 Third, this Court has not addressed standing-through-inseverability in any detail, largely relying on it through implication. See post, at 16– 20; Steel Co. v. Citizens for Better Environment, 523 U. S. 83, 91 (1998) (“We have often said that drive-by jurisdictional rulings . . . have no precedential effect”). And fourth, this Court has been inconsistent in describing whether inseverability is a remedy or merits question. To the extent the parties seek inseverability as a remedy, the Court is powerless to grant that relief. See Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Assn., 584 U. S. ___, ___–___ (2018) (slip op., at 3–4) (THOMAS, J., concurring); see also Barr v. American Assn. of Political Consultants, 591 U. S. ___, ___, n. 8 (2020) (plurality opinion) (slip op., at 16, n. 8). Thus, standing-through-inseverability could only be a valid theory of standing to the extent it treats inseverability as a merits exercise of statutory interpretation. See Post, at 15–16 (ALITO, J., dissenting); Lea, supra, at 764–776. But petitioners have proposed no such theory.

As a result, Thomas concludes, the court has finally managed to get an ObamaCare ruling correct on its third try:

The plaintiffs failed to demonstrate that the harm they suffered is traceable to unlawful conduct. Although this Court has erred twice before in cases involving the Affordable Care Act, it does not err today.

This challenge always looked better in theory than it did in practice. At this point, nine years after the first Supreme Court ruling, there is also a reliance interest involved here. Neither the governing opinion nor the dissent (or Thomas’ concurrence) discuss that, in large part because the issue of standing pre-empts everything else. But even if standing could be resolved, the attempt to demolish the whole act through the zeroing out of the mandate penalty was a long shot, especially since Congress clearly had an opportunity to revoke the whole bill at the time but chose to amend it instead. That itself suggests severability in Congress’ intent, an interesting side effect of Republicans’ efforts to kill off the mandate penalty in 2017.

That should bring the legal challenges to the Affordable Care Act to an end. Even the most conservative jurist on the Supreme Court isn’t inclined to indulge judicial activism to kill it. If Republicans want to get rid of the ACA, they’ll have to do so in Congress — and they’ll need to come up with a better alternative first. How’s that coming along, by the way?

Join the conversation as a VIP Member