Anthropogenic climate change may or may not be a thing. On this point I am open-minded and I keep reading the scientific literature.

I am inclined to think that the weight of evidence and logic suggests that human behavior is having a mild and generally unconcerning effect on the climate, but one that is swamped by other variables over which we have little to no control.

Historically speaking humanity has dealt with and overcome dramatically greater changes to our environment caused by natural variability in climate, weather, and geological events (earthquakes, volcanos, and suchlike), and we have adapted to environments that until recently were considered far too hostile for most people to tolerate.

Phoenix, for instance, is the fastest-growing city in the country. Nobody would live there without air conditioning and water management. Las Vegas was pretty much a nothing town in the middle of a desert until people turned it into an oasis of sin. Israel is one of the less forgiving places on Earth but has been turned into a thriving state through the ingenuity of its people.

In other words, anthropogenic climate change presents no serious threat to human beings. And as for the ecosystem? Compare any predicted climate change caused by human beings to the changes that have taken place naturally over the past 15,000 years, when North America, Europe, and much of Asia were covered by glaciers a mile thick. Believing that a degree or two of warming could be more dramatic than the ecosystem than the melting of the glaciers is the mark of an insane mind.

Whatever.

One of the reasons why I disdain most climate alarmists has little to do with their ridiculous assertions, and everything to do with their insistence on lying. Being wrong is no sin. Lying to get your way is a huge one, especially when you lie in order to seize power and destroy others’ lives.

One of the biggest lies we hear every hurricane season is that climate change is increasing the frequency and/or intensity of hurricanes. This assertion is pounded into us relentlessly, and millions of people believe it. They see the video, hear the “experts,” are propagandized about a false “consensus,” and are told that skeptics are like Holocaust deniers.

It’s BS.

You don’t have to trust me. You can get that straight from the horse’s mouth: the National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration.

NOAA puts out “State of the Science” fact sheets, and they have a recent one on hurricanes and climate change.

They released a new one in May this year, and while it assumes that anthropogenic climate change is real it also throws cold glacier-melt water on the assertion that there have been measurable increases in hurricane activity or intensity caused by carbon emissions.

The data isn’t there. They don’t deny the possibility that there may have been some very minor, undetectable effect, but the signal-to-noise ratio is such that it cannot be detected. Natural variability is far greater than anything human beings may or may not have done. They aren’t even sure if increases in global temperatures would lead to an increase or a decrease in either frequency (a decrease is more likely than not) or intensity (an increase is slightly more likely than not).

Several measures of historical Atlantic hurricane activity, including annual numbers of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes, as well as hurricane intensities, power dissipation index (PDI), and rapid intensification occurrence, all show pronounced increases since around 1980. Since the 1940s and 50s, major hurricane annual counts and related measures have shown pronounced multidecadal variations, including a major hurricane “drought” lasting from the 1970s through the mid-1990s. An increase in stalling near-coastal U.S. tropical cyclones and increases in accumulated rainfall during such stalls has been observed since about 1950. On the century time scale (e.g., since 1900) there has been no significant trend in annual numbers of U.S. landfalling tropical storms, hurricanes, or major hurricanes (Fig. 1). A decreasing trend since 1900 in the propagation speed of tropical storms and hurricanes over the continental U.S. has been reported. Basin-wide annual counts of tropical storms, hurricanes, and major hurricanes since the late 1800s show strong rising trends, but after taking into account changes in observing capabilities, studies suggest no strong evidence for a significant upward trend in any of these basin-wide storm count metrics (Fig. 1).

In other words, things change quite a bit over long time scales. Sometimes there are a lot of hurricanes, other times there are very few. Even intensity changes quite a bit. Looking for any trend on a short time scale is a fool’s errand, and no matter how much you want to find one there is no evidence that it exists and no easy way to find one if it does. If there are huge swings on the multi-decadal time scale and on the century time scale (we have no longer-term data to even go back very far) any claims that a signal has been detected is a lie.

And I choose that word carefully because we are being told constantly that the “science” tells us something that it simply cannot. This is not a mistake. It is a lie. All you need to do is ask NOAA–I found this in less than 5 minutes of Googling.

Observed hurricane data generally either do not show clear centennial-scale trends or do not cover enough years to assess century-scale trends. Pronounced multidecadal variations typically dominate over long-term (centennial- scale) trends over decadal timescales for Atlantic hurricanes. One statistical study concluded that the probability of extreme tropical cyclone rainfall events like that during Hurricane Maria has increased over parts of Puerto Rico since 1956 due to long-term climate change. However, recent observed increases (e.g., since 1980) in Atlantic hurricane activity are generally not representative of longer-term (70-year to centennial-scale) trends, in cases where such longer-term records are available. Rather, trends since 1980 appear to represent the latest upswing in a series of multi-decadal variations, leaving open the question of what caused the multi- decadal swings.

Most of the time when you hear references to “The Science” the person making the claim is referring to The Model, and the model in each case is cherry-picked to arrive at a pre-determined conclusion. As you can see from what NOAA says in their brief, any model that relies on the available data is basically putting in garbage and hence spitting out garbage. One of the great limitations when discussing hurricanes, for instance, is that most of them were not recorded until recently unless they made landfall. Satellites changed that to a great extent and as our data improved the number of detected tropical storms increased. That is an artifact–as they say–of the data collection.

Another complication is that the late 20th century experienced a major lull in hurricane activity and that there has been a reversion to the mean. This paper in Nature discusses this and it also suggests that attribution of any changes to climate change is not warranted by the data.

Due to changes in observing practices, severe inhomogeneities exist in this database, complicating the assessment of long-term changes7,8,9,10,11,12,13. In particular, there has been a substantial increase in monitoring capacity over the past 170 years, so that the probability that a HU is observed is substantially higher in the present than early in the record10; the recorded increase in both Atlantic TC and HU frequency in HURDAT2 since the late-19th century is consistent with the impact of known changes in observing practices7,8,9,10,11,12. Major hurricane frequency estimates can also be impacted by changing observing systems13.

We here show that recorded increases in NA HU and MH frequency, and in the ratio of MH to HU, can be understood as resulting from past changes in sampling of the NA. We build on the methodology and extend the results of ref. 10 to develop a homogenized record of basin-wide NA HU and MH frequency from 1851–2019 (see Methods Section), this homogenized record indicates that the increase in NA HU and MH frequency since the 1970s is not a continuation of century-scale change, but a rebound from a deep minimum in the late 20th century.

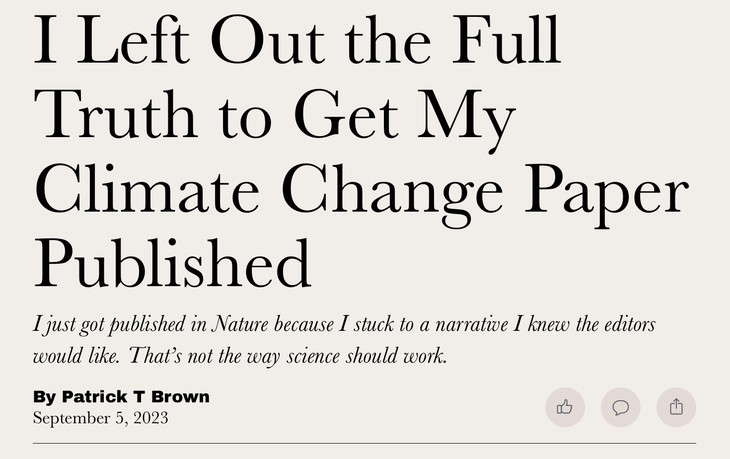

Ed wrote yesterday about a piece published in The Free Press about why climate-related papers tend to emphasize scary scenarios when discussing climate. Written by a climate scientist who had just published a paper in Nature he explains why he left out important context in his paper in order to get it published.

He didn’t fake data. He didn’t cook the books. He didn’t lie. He simply omitted facts that the editors and his peer reviewers wouldn’t want to have emphasized.

The paper–on wildfires and climate change–was an honest assessment of his study. But it also left out the fact that the effect of climate change on wildfires was minuscule compared to other variables and irrelevant to the overall frequency and effect of wildfires. Since most wildfires–80%–are set by human beings intentionally or unintentionally, any minor climate variability is swamped by other factors.

So why does the press focus so intently on climate change as the root cause? Perhaps for the same reasons I just did in an academic paper about wildfires in Nature, one of the world’s most prestigious journals: it fits a simple storyline that rewards the person telling it.

The paper I just published—“Climate warming increases extreme daily wildfire growth risk in California”—focuses exclusively on how climate change has affected extreme wildfire behavior. I knew not to try to quantify key aspects other than climate change in my research because it would dilute the story that prestigious journals like Nature and its rival, Science,want to tell.

This matters because it is critically important for scientists to be published in high-profile journals; in many ways, they are the gatekeepers for career success in academia. And the editors of these journals have made it abundantly clear, both by what they publish and what they reject, that they want climate papers that support certain preapproved narratives—even when those narratives come at the expense of broader knowledge for society.

To put it bluntly, climate science has become less about understanding the complexities of the world and more about serving as a kind of Cassandra, urgently warning the public about the dangers of climate change. However understandable this instinct may be, it distorts a great deal of climate science research, misinforms the public, and most importantly, makes practical solutions more difficult to achieve.

It is all about The Narrative. Even when reading true information from truthful scientists you cannot be sure that you are getting the full story. And without the full story, it is impossible to get a sense of what is going on.

So here we are. In a world where science is utterly compromised.