One of the greatest inventions of mankind is the scientific method. Without it, mankind would be left infinitely poorer both materially and intellectually.

But like any tool, it has its limitations. We’ve seen this time and again. Tools are useful when used properly in skilled hands, and dangerous when not.

One of my favorite examples of this phenomenon is the how scientists have tried to us their methods to understand complex natural systems. In principle, the idea is a good one, but once the scientific method is married to scientists’ hubris great damage is done. What makes natural systems so difficult is our inability to test models.

The best example is the science of nutrition. Early advances in understanding nutrition led to tremendous benefits. Discovering the importance of basic nutrients like iodine, vitamin C, the B vitamins, and vitamin A was huge. Eliminating Scurvy, Rickets, Beriberi, Hypocalcemia, Osteomalacia, Vitamin K Deficiency, Pellagra, Xerophthalmia, and Iron Deficiency has led to tremendous increases in human well being. Kudos!

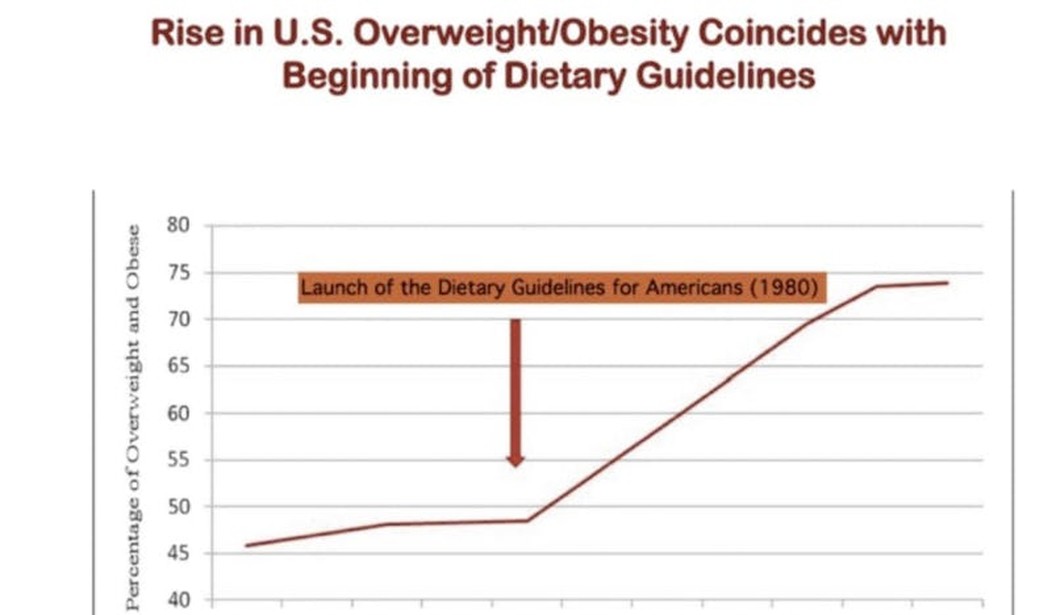

But nutrition science on the whole since the identification of vitamins has gifted us obesity, rampant Diabetes II, a stupid war against dietary cholesterol, a food pyramid that has worsened health, and insane government advice on how to eat. Drink coffee, don’t drink coffee…. Nutrition advice can be maddening, changing by the moment. Is salt OK or not?!

The latest example of this–and don’t worry, I’ll get to how this relates to the scientific method in a bit–is Tufts University’s “Food Compass.” Developed with funding from the National Institutes of Health, the Food Compass is the modern version of the “food pyramid” which did so much to help Americans get obese.

The “food compass” is an attempt to develop a simple scale to determine what foods should and should not be consumed based upon a nutritional profile of each product. The scientists involved put together a profile of various foods based upon the nutritional content, rating them on a scale of 0-100.

Foods that are good for you are rated closer to 100, bad closer to 0. The general idea is simple enough: encourage people to include more foods rated highly and fewer rated towards the bottom.

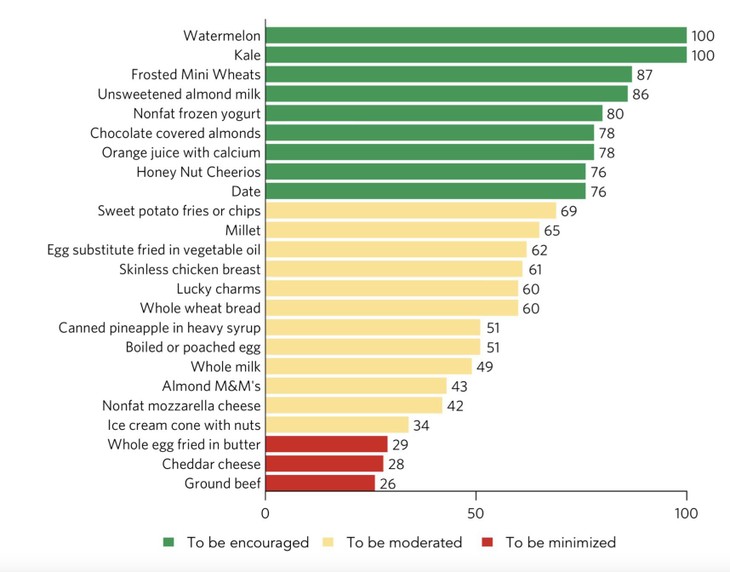

So how do the food ratings look? Well here is an example of what Tufts’ Food Compass tells us:

Foods in green are “to be encouraged,” and foods in red are “to be minimized.” From this we learn that a breakfast of Frosted Mini Wheats or Honey Nut Cheerios is vastly better than an egg or two in the morning, especially if you make an omelette with cheddar cheese.

Lucky Charms, in fact, is better than a poached egg. And God forbid you eat ground beef instead of canned pineapple in heavy syrup. You are likely to die right away.

Now either you can accept that Tufts has discovered that a diet high in ultra-processed foods is really great for you, or you have discovered a glaring flaw in the lessons that people can take from a reliance on “science” without understanding its limitations as a mode of enquiry.

On the one hand, the Tufts approach makes perfect sense from a scientific point of view. The scientific method requires breaking complex phenomena into simpler pieces that can be turned into variables that can be manipulated. In this case the nutritionists did so by isolating nutritional characteristics like vitamin content, fibre content, protein, carbs, etc. Separate each of these variables and you can manipulate them independently.

This is the same sort of thing that physicists do when they describe a phenomenon like gravity. We’ve all seen the experiments showing the feather and the bowling ball falling at the same rate in a vacuum, proving that gravity exerts the same force on each item.

The difference, though, is that the experiment only works in a vacuum. Drop a feather and a bowling ball in the “real world” where atmosphere exists and you get a very different result. The feather, caught by a gust of wind, can get blown off into the distance. Try that kind of experiment with nutrition–eliminate all the confounding variables. You can’t. The system is too complex and interrelated. You can’t abstract the variables.

Tufts’ nutrition science ignores the “atmosphere,” treating the elements of nutrition as if the whole of one’s diet is simply the sum of all the variables they isolated. But clearly that isn’t the case.

A varied diet of whole foods, with minimal processed foods, is clearly better for you than anything concocted out of this sort of analysis. No serious nutritionist would be recommending a diet composed of Frosted Mini Wheats and Lucky Charms over a balanced diet that included meat, eggs, and cheese as components. The reverse should be the case.

A scientist who was not driven by hubris–and obviously there aren’t enough of them–would look at the results spat out by this “Food Compass” and use his common sense to realize that it is telling us things that are clearly insane. Instead, like a bad programmer they just accept the results spat out by the computer as gospel.

This is scientism. Trusting the process, regardless of how absurd the results are.

Science works through the process of abstraction. Take a very complex phenomenon and simplify it until you can model it. Then you test the model to see how well it mirrors the phenomenon you are investigating.

Done right, this is extremely powerful. Done badly, it can take you down some ridiculous rabbit holes. In nutrition it has done the latter, time and again. The introduction of the USDA guidelines decades ago led to a skyrocketing in the consumption of carbs, leading to the obesity crisis today.

Bodies are complex, and unsurprisingly it is very difficult to break down something like nutrition into clear cut variables that you can tweak to get the results you want. Especially when it is nearly impossible to check your work. There is no good way to test the models, since doing so requires randomized controlled studies over decades. In most scientific endeavors you can refine your models until they match observations. Here? Not so much.

So they shoot from the hip instead.

Giving advice like this can be dangerous, since getting it wrong can cost lives.

With nutrition (as, I would argue, with climate), the models will never work because identifying the variables and how they interact is way too complex to simplify. The best we can do is look at population level studies and tease out correlations. Eating fish appears to be good for you. Refined grains and sugars sure seem bad. Fruits and vegetables appear to be good for you…. Don’t follow the government’s advice ever…

It’s not that we can’t learn anything through scientific studies in nutrition–it’s that there are limitations in complex systems with a nearly infinite number of interacting variables. Simplify things too much and the model becomes useless. Most studies are worthless–we know that because they all contradict each other.

This model–the “Food Compass”–looks worse than useless to me, in the way that the original “Food Pyramid” was worse than useless.

If your model says that eating Lucky Charms or Almond M&Ms is better than having a slice of Cheddar Cheese, time to start over.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member