I grudgingly admire this dude’s willingness to go all-in on his position after having been scolded last week by half the lawyers on the Internet. If you’re out to censor your political opponents on “hate speech” grounds, you can’t let some clucking by First Amendment experts frighten you.

He mentions three cases that supposedly make Ann Coulter’s right to speak at Berkeley a “close call” which ultimately can be infringed on “safety” grounds or whatever. One is the Chaplinsky decision from 1942, in which the Supreme Court held that “fighting words” can be banned because they’re likely to lead to violence. The second is the Snyder v. Phelps decision from a few years ago, when an 8-1 Court upheld the Westboro Baptist Church’s right to picket a fallen soldier’s funeral. The third is the 2002 decision in Virginia v. Black, when the Court ruled that certain types of cross-burnings can be prohibited by the state. Here’s what happened in that case:

On May 2, 1998, respondents Richard Elliott and Jonathan O’Mara, as well as a third individual, attempted to burn a cross on the yard of James Jubilee. Jubilee, an African-American, was Elliott’s next-door neighbor in Virginia Beach, Virginia. Four months prior to the incident, Jubilee and his family had moved from California to Virginia Beach. Before the cross burning, Jubilee spoke to Elliott’s mother to inquire about shots being fired from behind the Elliott home. Elliott’s mother explained to Jubilee that her son shot firearms as a hobby, and that he used the backyard as a firing range.

On the night of May 2, respondents drove a truck onto Jubilee’s property, planted a cross, and set it on fire. Their apparent motive was to “get back” at Jubilee for complaining about the shooting in the backyard. Id., at 241. Respondents were not affiliated with the Klan. The next morning, as Jubilee was pulling his car out of the driveway, he noticed the partially burned cross approximately 20 feet from his house. After seeing the cross, Jubilee was “very nervous” because he “didn’t know what would be the next phase,” and because “a cross burned in your yard … tells you that it’s just the first round.”

The Court had held years before that the First Amendment prevents the state from outlawing cross-burning in all circumstances. But when, as in Virginia, the statute is limited to cross-burning with an “intent to intimidate,” then the act can be punished the same way any “true threat” aimed at another person can be punished. If the Klan wants to burn a cross at a rally, they can do that, the Court noted, because that’s an expression of political ideology. But do it in the yard of a black neighbor who reasonably fears that your hostility will escalate into a threat on his life and that’s different. The same circumstantial logic applies in Chaplinsky: “Fighting words” uttered face to face during a confrontation can be banned, the Court has held, but once you remove the risk of imminent violence those words become protected speech. That element of imminence also factored into Brandenburg v. Ohio, when the Court held that speech can be banned as incitement to violence if it’s “directed at inciting or producing imminent lawless action” and such action is “likely” to result. You can’t egg on an angry crowd to riot and you can’t send the neighbor you’re feuding with a letter that reads “you’re dead.” But short of that? You’re pretty well covered.

What’s ominous about Dean’s shpiel below is that he wants to do away with the circumstantial nature of exceptions to the First Amendment and make them more categorical. Ann Coulter once said years ago that she wishes Timothy McVeigh had targeted the New York Times building instead? Well, then, that’s reason to bar her from Berkeley now, never mind that it wasn’t a “true threat” and certainly wasn’t incitement under the Brandenburg test. Here’s another example of wanting to ban her for something she said long ago:

Coulter: I'd like to see 'a little more violence' from Trump supporters https://t.co/e1uCaSQHPe

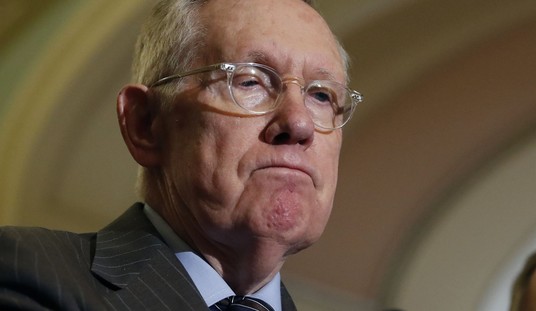

— Howard Dean (@GovHowardDean) April 23, 2017

This is NOT protected speech under the first amendment. Check Chaplinsky V New Hampshire SCOTUS 1942. https://t.co/wr3rMaRnAB

— Howard Dean (@GovHowardDean) April 23, 2017

This does not mean she can be prosecuted for saying this but I argue this kind of stuff is grounds for barring her from a University campus https://t.co/7TkRFTHBp2

— Howard Dean (@GovHowardDean) April 24, 2017

What Coulter actually said back in March, after a Trump rally was shut down by left-wing provocateurs, was “I would like to see a little more violence from the innocent Trump supporters set upon by violent leftist hoodlums.” That’s a particularly bad example for Dean to cite since it wasn’t so much incitement as a call for self-defense after provocation by the other side, an example of how capricious the standards for “hate speech” tend to be, but in any case it wasn’t remotely illegal under the Chaplinsky or Brandenburg tests. The difference between Dean’s thinking about offensive speech and the Supreme Court’s thinking is that the Court is worried about situations where the dynamic is already dangerous and at risk of turning violent — the angry crowd, the feuding neighbors — whereas Dean is worried about a dangerous dynamic developing in reaction to the speaker herself. The Court’s logic towards threats and incitement is “don’t make a bad situation worse by saying something irresponsible”; Dean’s logic is “don’t say something irresponsible or you’re apt to create a bad situation.” Big difference. If you follow the Dean model, any “irresponsible” speaker can be sanctioned indefinitely. And lord only knows how “irresponsible” would be defined.

Exit question: Are there any free-speech champions left on the left? Exit answer: Yes. Bernie!

Howard Dean on Ann Coulter: 'It's actually true' the First Amendment doesn’t protect "hate speech" pic.twitter.com/N7s0HTOOdI

— Tom Elliott (@tomselliott) April 23, 2017

Join the conversation as a VIP Member