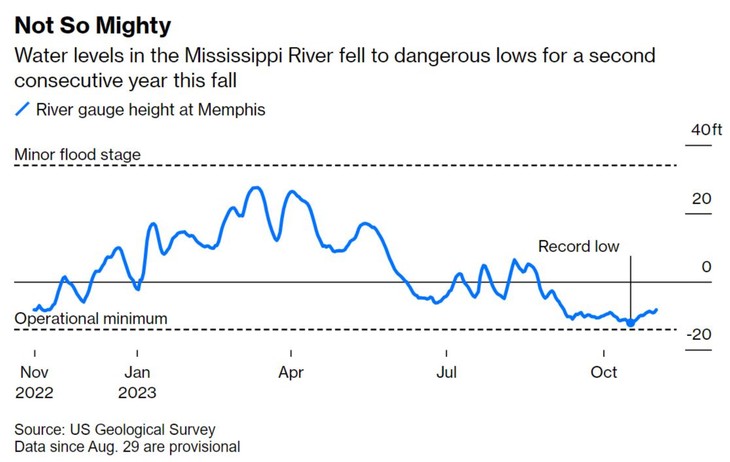

Wow. After following this all last fall, I thought there’d been a bit of a recovery. There were those storms that brought the massive snowpack to the Rockies and Sierra Nevadas rolling across the plains into the Mississippi headwaters, or so I figured. But I guess I was wrong and also hadn’t paid much attention to a pretty dry summer.

So it’s been two years of drought and only dredging is keeping the river channel open in some really low spots.

It’s been so low, there’s been a plume of saltwater intrusion making its way upriver from the Gulf into the New Orleas area. Not only is that a problem for freshwater wildlife, it’ll impact wells and drinking water delivery for parts of the city and surrounding parishes.

A new saltwater forecast for the New Orleans area is out. Check the latest.

A new forecast released Thursday further slows the advance of saltwater intrusion in the Mississippi River, leaving all of New Orleans and Jefferson Parish outside areas of concern while adding Belle Chasse to locations expected to avoid contamination.

The forecast through Dec. 27 released by the Army Corps of Engineers predicts no additional communities will face concerning levels of salt in drinking water beyond those already dealing with the problem. Salt had been predicted to reach intakes in Belle Chasse around Nov. 30, but the latest forecast keeps it in the clear.

Saltwater contamination is expected to remain at plants in Boothville, Port Sulphur and Pointe a la Hache in Plaquemines Parish for at least the next month. Plaquemines has been dealing with the problem for months, and has used barged water to dilute salt at intakes. Drinking water advisories for all affected areas in Plaquemines were lifted on Oct. 18.

The city and Army Corps of Engineers has a $250M pipeline in the works to deal with the problem, but it’s on hold at the moment because their emergency fixes and higher water seem to be keeping the saltwater at bay. And they have done some extraordinary things already.

…The river’s water levels have fallen to a point that it can’t flow with sufficient force to push back salt water from the Gulf of Mexico. As a result, the Army Corps of Engineers has been called into resupply water treatment plants in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, which has been overwhelmed by an influx of salt water.

The Army Corps, which already constructed a salt sill in the lower river, is now shipping fresh water from upstream to Plaquemines, on the extreme southeastern tip of Louisiana where the river meets the Gulf. The Corps has delivered 500,000 gallons by barge to the Port Sulphur Water Treatment plant to dilute the Mississippi’s salinity there, it said in a statement.

Severe drought has caused water levels in the Mississippi River to drop so low that ships have been running aground. To keep commerce flowing, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is now using a dredge ship to push out silt in the river near Vicksburg, Mississippi.

The chief of… pic.twitter.com/Gq4mqOFCxn

— Laufer Group International (@LauferGroup) November 1, 2023

There’s not much hope for relief from upstream, either, as even the Ohio River was running at low levels by October.

…Drought across the central US and Midwest have left water levels low on not only the Mississippi but also its tributaries, such as the Ohio River. At Cairo, Illinois, the Ohio River is in its low water stage. Through September 26, nearly 55% of the Midwest was gripped by drought, with almost 66% of South also dry, according to the US Drought Monitor. More than 99% of Louisiana was in drought, according to the US Drought Monitor.

As I learned last year, this couldn’t come at a worse time, because fall is the start of the wheat and grain shipping season for the Mississippi, and barges are the only efficient and timely way to get the massive quantities downstream to Gulf seaports for shipping overseas. Farmers are scrambling for alternative transportation.

Low Mississippi River water levels could disrupt grain harvest again, posing a threat to farmers and the grain industry. With 60% of U.S. grain exports transported via the Mississippi River, it's crucial to find alternative modes of transportation. Read: https://t.co/q1mIAouRr4 pic.twitter.com/kJQsxSwu4P

— AssuredPartners Inc. (@AssuredPartners) November 6, 2023

It was already bad by late September…

A key stretch of the lower Mississippi River dropped this week to within inches of its lowest-ever level and is expected to remain near historic lows just as the busiest U.S. grain export season gets underway, according to the National Weather Service.

Low water has slowed hauling of export-bound corn and soybean barges over recent weeks as shippers lightened loads to prevent vessels from running aground and reduced the number of barges they haul at one time to navigate a narrower shipping channel.

The water woes come at the worst possible time for U.S. farmers as newly harvested corn and soybeans are beginning to flood the market and as stiff market competition from Brazil has already eroded once-dominant U.S. exports.

Portions of the river have been closed 22 times since Sept. 1 for dredging or to remove barges that have run aground, and at least 36 groundings have been reported, the U.S. Coast Guard said.

…and it’s killing American wheat exports now, losing this country and her farmers their much coveted “status as the shipper of choice.”

American wheat shipments dropped to the lowest ever, hampered by a shrinking Mississippi River and competition from ample global grain supplies.

…Export inspections of American wheat in the week ended Nov. 2 totaled only 71,608 metric tons, with some wheat shipped from Duluth, Minnesota, through the Great Lakes but virtually nothing on the Mississippi River, according to the US Department of Agriculture. That is the smallest total on record in weekly USDA data going back to 1983.

Mississippi water levels improve slightly from last month’s record low, but world crop buyers have already beenbuying more supplies from elsewhere. It is limiting demand for U.S. grain w/exports at a 20 year low contributing to the country losing its status, as shipper of choice

— Day Trading Academy (@DTradingAcademy) November 8, 2023

We’re going into what looks to be a robust El Niño right now, which means there won’t be any relief in sight weather-wise. Midwest winters during an El Niño tend to be drier across the region and up into the Great Lakes – not helpful.

That has to be piling on the concerns across the board.

…That forecast trend is unfavorable when it comes to the prospect of any improvement in soil moisture. The NOAA report noted, “Much of the Midwest is entering winter with below-normal soil moisture, so drier conditions due to El Nino may slow drought recovery. Additionally, reduced snowpack can expose crops to harsh winds and cold air outbreaks.”

Snowfall differences from average in the Midwest during moderate-to-strong El Nino events are significant. In the 1959-2023 period of record, the Midwest winter snowfall totals in the winters with moderate-to-strong El Nino events are generally from 6 to 10 inches below average. Those departures are highly significant in the eastern Great Lakes and the upper Ohio River Valley. This suggests lake-effect snow will be lower this coming winter than in a year without a moderate-to-strong El Nino on the scene.

This is gruesome and the very last thing either American agriculture or the American consumer needs.

Wrap it in a #Bidenomics bow and it could get really fugly.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member