Frequently when I write about things I’ve read at Vox it’s to criticize them for being awful. But that’s not always the case. Sometimes they do publish something genuinely interesting. Such is the case today where Dylan Matthews has an interview with author Julia Galef who has written a book about thinking called The Scout Mindset. I haven’t read the book so this isn’t a review or a recommendation but I thought the concept was interesting. Here’s Galef explaining what the scout mindset means:

By default, a lot of the time we humans are in what I call “soldier mindset,” in which our motivation is to defend our beliefs against any evidence or arguments that might threaten them. Rationalization, motivated reasoning, wishful thinking: these are all facets of what I’m calling a soldier mindset.

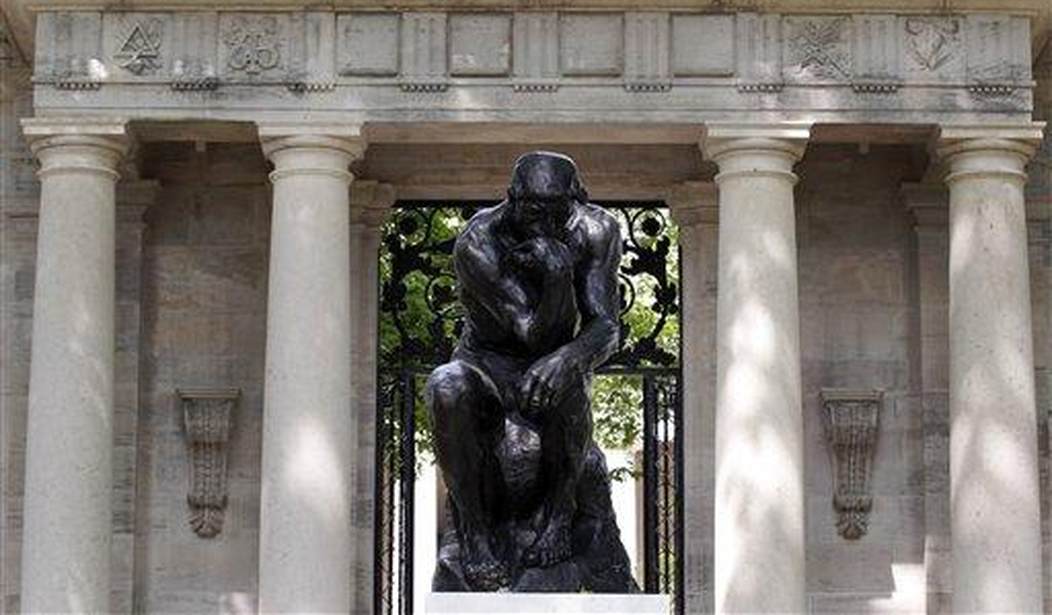

I adopted this term because the way that we talk about reasoning in the English language is through militaristic metaphor. We try to “shore up” our beliefs, “support them” and “buttress them” as if they’re fortresses. We try to “shoot down” opposing arguments and we try to “poke holes” in the other side.

I call this “soldier mindset,” and “scout mindset” is an alternative to that. It’s a different way of thinking about what to believe or thinking about what’s true.

One of the reasons I find this interesting is that it brings me all the way back to the very beginning of Vox when co-founder Ezra Klein wrote an article which was very pessimistic about cultural cognition and the ways it shapes politics. The article wasn’t just informational, at least I didn’t take it that way. It was intended as a kind of promise that Vox would do its best to avoid the pitfalls of cultural cognition.

Now here we are seven years later and Klein has moved on to the NY Times and co-founder Matt Yglesias has moved on to Substack after some of his colleagues at Vox complained he was straying a bit too far from progressive orthodoxy. Frankly, anyone who reads Vox should already know that it frequently failed to live up to its own attempt at rising above cultural cognition. It was often intentionally, sometimes stupidly, provocative and had a tendency to sidestep arguments that might undercut a progressive narrative.

All of that to say, this piece about the scout mindset is in some ways an attempt to circle back (as Jen Psaki might say) to something that was initially promised to be a major commitment at Vox. But even in this interview, Galef admits that a lot of the time, discussion of these issues is just a way to criticize the other team:

if you think about the people you’ve seen online who know a lot of cognitive biases and logical fallacies, and you just ask yourself, “Do these people tend to be really self-reflective?” — I don’t think they usually do, for the most part.

The people I see who talk a lot about people engaging in cognitive biases and fallacies prefer to point out those biases and fallacies in other people. That’s how they wield that knowledge.

Even when you’re motivated to try to improve your own reasoning and decision-making, just having the knowledge itself isn’t all that effective. The bottleneck is more like wanting to notice the things that you’re wrong about, wanting to see the ways in which your decisions have been imperfect in the past, and wanting to change it. And so I just started shifting my focus more to the motivation to see things clearly, instead of the knowledge and education part of it.

In other words, you can hand someone a mirror but they might use it solely to hit people over the head. The only way to make this work is to focus on the motive. For Galef, that means not letting herself react the way she instinctively wants to when a challenge is presented but forcing herself to first consider the possibility of being wrong:

Sometimes if I’m reading criticism and I’m feeling stressed out and defensive, and I notice that I’m reaching for rebuttals of it, I will just stop and imagine, “What if I found out that this critique was actually solid? How bad would that be?”

What I realized in that moment is, “I guess that would be okay. It’s happened before, and wasn’t the end of the world. Here’s what I would say on Twitter in response to the article, here’s how I would acknowledge that they made a good point.”

It really is a hard thing to do. It’s very easy to get pushed into that soldier mindset, especially when you see someone attacking you or someone you know. It’s very hard to dial it back and try to be generous to someone’s argument when you can already see three ways in which they are clearly wrong.

A lot of it has to do with social media, especially Twitter. Twitter is supposed to be a place for conversation but it’s often a place where people trade shots. And then each team celebrates victories and whines about losses. And the fact that it’s all public means there’s a need on all sides to avoid losing face. It’s one thing to admit you have doubts about this or that in private. It’s another to do it in public when your whole team (potentially) is watching. The whole process weeds out people who want to actually have a conversation about whatever in favor of those who just want to engage in the 21st century rhetorical equivalent of stick-fighting. And I’ve been guilty of this as well. Some people really just get on my nerves and I can’t always hide it.

Anyway, take all of that for what you will. My guess is that many of us are more reasonable and far more interesting than we often appear to be online. That’s not to say there aren’t things worth fighting for or that there aren’t times when the best answer is to simply say no to someone else, especially when they are only interested in compliance and not conversation. Still, I find the idea of the scout mindset appealing in some ways even as I’m fully aware how some overly-online people (who are always in soldier mode) would take it for weakness.