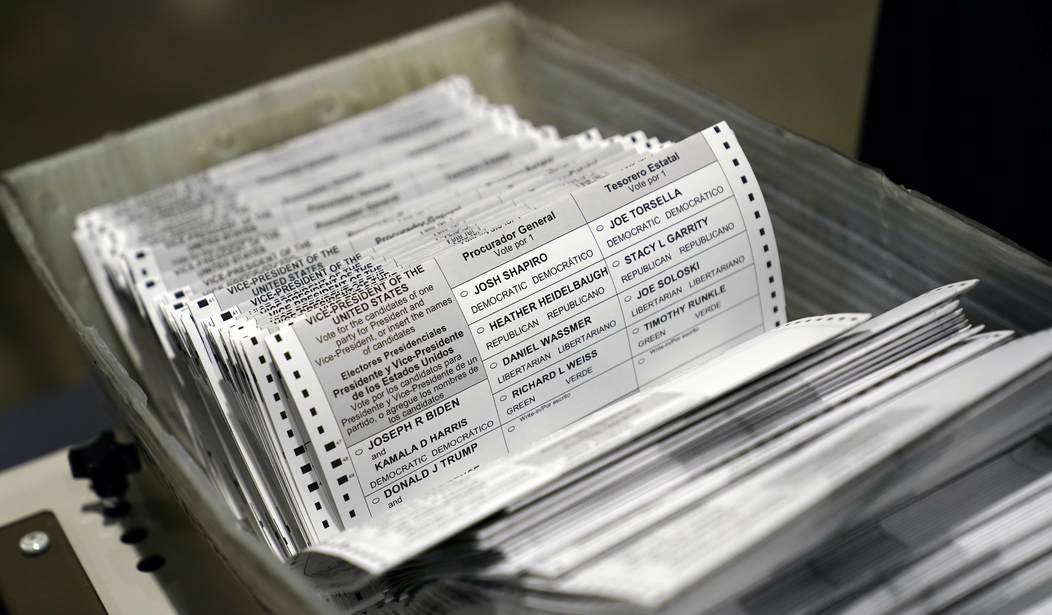

In Minneapolis yesterday, 34-year-old Muse Mohamud Mohamed was convicted on three counts of what basically amounted to voter fraud. What he was technically convicted of was lying to a federal grand jury that was investigating potential irregularities in the 2020 elections, but it works out to be the same thing. Mohamed submitted three ballots in the Democratic primary for other people, claiming to be their authorized “agent” and acting on their behalf because they were unable to cast the ballots themselves. The reason that the jury took less than an hour to convict him is that all three of the “voters” in question testified that they didn’t even know the man and had not given him an absentee ballot to submit. And one of the people had already voted in person. (Associated Press)

A Minneapolis man was found guilty Tuesday of lying to a federal grand jury about abusing a process for submitting absentee ballots for other voters during Minnesota’s primary election in August 2020.

After a day of testimony, the jury of 10 women and two men took just 40 minutes to convict Muse Mohamud Mohamed of two counts of making false statements to a grand jury, according to Minnesota Public Radio.

Mohamed, 34, was accused of falsely telling the grand jury last fall that he had obtained three absentee ballots for the primary on behalf of three voters who then filled them out before he returned them to the election office.

There have been so many of these cases cropping up all over the country ever since Democrats began pushing for massive mail-in voting that the flaws in these systems should be obvious by now. Minnesota’s voting laws contain a provision for “agent delivery.” If a person wishes to vote but is unable to do so due to illness or disability, they can assign an “agent” to take their ballot and drop it off, even after the voting deadline. An agent is allowed to deliver up to three ballots in this fashion.

Mohamed was a volunteer for a Democratic Socialist candidate named Omar Fateh, who was running in the primary for a state senate seat. Fateh went on to win the primary by just 2,000 votes and then the general election. What Mohamed was doing seems obvious. He wanted to give the boss a bit of a boost, so he found the names of three registered voters in the district and filled out ballots in their names.

It appears that the only reason Mohamed was caught and eventually convicted was that the election was under review by the grand jury. The rest of the grand jury records are sealed, so even the AP admits that it remains “unclear” whether or not anyone else was or is under scrutiny for the same sort of illegal activity. But if one of Fateh’s volunteers thought this was a fine idea, what are the odds that others were attempting the same thing, potentially without being detected?

One of Mohamed’s three ballots wound up being rejected because the person identified on the ballot had voted in person. But the other two ballots were counted. The AP takes great pains to point out that those two ballots were “not nearly enough to affect the outcome.” But we’re talking about a state senate primary race here without a huge number of voters participating. How many people like Mohamed would it take before the outcome was actually impacted? And for that matter, how many illegal votes are we supposed to accept as being “no big deal” in any election? Shouldn’t the number be zero?

Massive mail-in voting, originally embraced only as a response to the pandemic lockdowns, is something that the Democrats are attempting to enshrine permanently on a national level with their stalled “voting reform” bills. But as we’ve seen too many times, this process opens the door to those who might be tempted to cheat. Once that door is open, people will inevitably walk through. And just as a reminder, these flawed mail-in voting schemes may have already flipped a congressional race in New York.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member