The number of people who have been charged in connection with the January 6th riot at the Capitol Building has now grown to over 500. Few of the accused have achieved the level of “fame” that Jake Angeli, the so-called Qanon shaman has achieved, but they are all facing a variety of charges ranging from disturbing the peace to vandalism, with a smaller number facing assault raps. Plea deals are being struck already, with some of the participants agreeing to cop to lesser charges to avoid a trial. But Michael Tarm of the Associated Press thinks he sees something missing from all of these proceedings. Why, he asks, has nobody been charged with sedition or treason? Here’s how he makes his case.

Plotted to block the certification of Joe Biden’s election victory: Check. Discussed bringing weapons into Washington to aid in the plan: Check. Succeeded with co-insurrectionists, if only temporarily, in stopping Congress from carrying out a vital constitutional duty: Check.

Accusations against Jan. 6 rioter Thomas Caldwell certainly seem to fit the charge of sedition as it’s generally understood — inciting revolt against the government. And the possibility of charging him and others was widely discussed after thousands of pro-Trump supporters assaulted scores of police officers, defaced the U.S. Capitol and hunted for lawmakers to stop the certification. Some called their actions treasonous.

But to date, neither Caldwell nor any of the other more than 500 defendants accused in the attack has been indicted for sedition or for the gravest of crimes a citizen can face, treason.

The events of January 6th were a travesty and the actions of many who broke into the building (as opposed to those who remained out in the streets and simply protested) were clearly criminal. But did they actually rise to the level of treason, or even sedition? Rioting, even on government property, doesn’t really sound like it rises to those levels or else we’d have a lot more treason and sedition cases going to court than we do these days. But let’s give Mr. Tarm the benefit of the doubt and explore this for a moment.

The definition of treason is pretty straightforward. It comes straight from the Constitution and is defined in Title 18 as “Whoever, owing allegiance to the United States, levies war against them or adheres to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort within the United States or elsewhere.” This is broadly understood to mean engaging in acts of war against the United States in support of our enemies. Both the terms “act of war” and “enemies” are considered by some to be vague enough to leave at least some room for interpretation, but I would argue not nearly as much as would be required here.

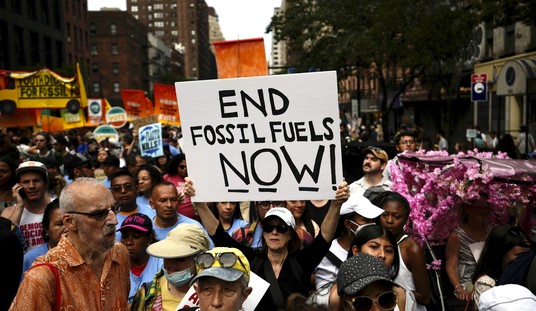

Treason isn’t typically understood to include “all enemies foreign or domestic.” It refers to actual warfare, which takes place between countries or organized subsets of countries in the case of civil war. Those are the “enemies” that come to mind when you throw around words like treason. If a couple of hundred people throwing bottles at the police and breaking into a building qualifies as war, then pretty much every BLM riot over the last couple of years was an act of war. And since they frequently attacked police stations and the police themselves – part of the executive branch of government – then they were all traitors too.

Sedition may be another matter, though. Seditious Conspiracy, as defined by code, covers a lot of territory. It begins by describing a situation where “two or more persons in any State or Territory, or in any place subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, conspire to overthrow, put down, or to destroy by force the Government of the United States.” While the rioters were, at least in some cases, working in concert with each other, their apparent goal was to prevent the certification of the 2020 election results. I somehow doubt you could make a very good argument in court that trying to force a different outcome to an election is the same as trying to completely overthrow or destroy the government attempting to hold that election.

But the code goes a bit further. Seditious Conspiracy can also be charged if two or more people “oppose by force the authority thereof, or by force to prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the United States.” That’s actually such a generic description that sedition could apply to a wide swath of criminal activities. If two people attempt to prevent a police officer from apprehending a suspect, allowing them to escape, that could be considered sedition, but we almost never charge anyone with that. (In 2010, members of the Hutaree militia in Michigan were charged with Seditious Conspiracy, but those charges were eventually thrown out.)

So yes, you could argue that the January 6th rioters were working together to prevent the execution of our election laws. But the question once again comes back to intent. Much like treason, you would have to prove that the purpose of the interference with the laws was to basically overthrow the government. I don’t believe a judge would entertain such a proposition. There are plenty of crimes associated with rioting that can be brought, not that you would know it from the curious lack of prosecutions and convictions of BLM rioters. And those are most likely the ones you’ll see going forward with these defendants.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member