What role should Congress — or for that matter, the federal government in general — play in setting terms between workers and management? Does the nature of the industry matter to that question in a free-market economy where collective bargaining is robust?

The answer to this question may depend on how one approaches the labor impasse in the rail industry and the prospect of a crippling strike. One can approach it morally, legally, economically, and/or politically.

And the answer really should be no in every case — even if just on practical terms.

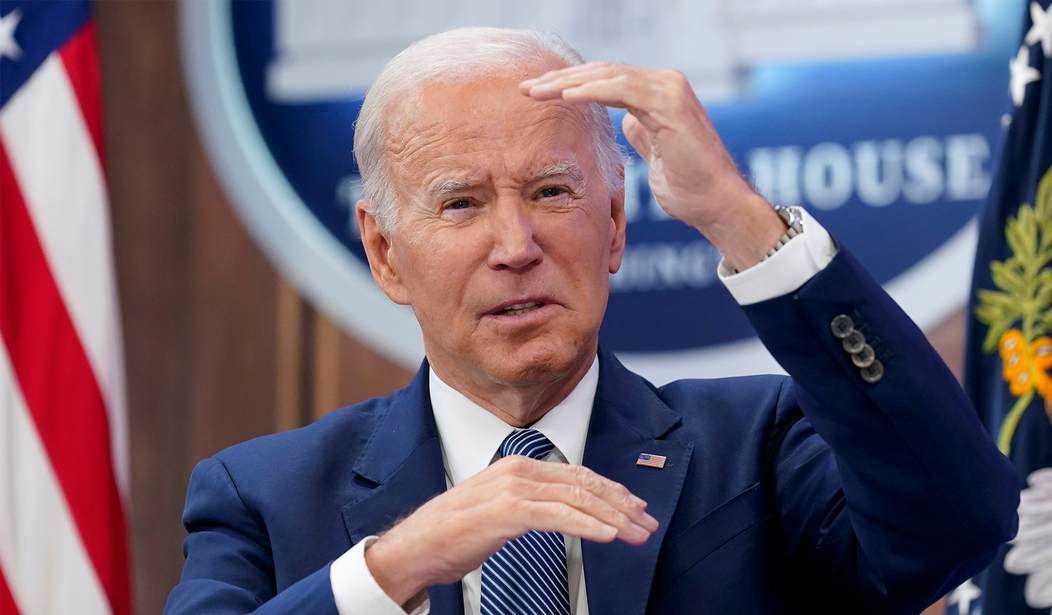

The House and Senate find themselves in this position because of Joe Biden’s incompetence and dishonesty. Biden intervened in the rail-labor dispute to give a new set of arbitrators several weeks to come up with a solution to an impasse. Biden’s team came up with a deal that somehow failed to address one of the most understandable worker complaints in the mix: a refusal to include any sick days for workers in the national contract. Nevertheless, union negotiators accepted the deal — which also included a 24% overall increase in compensation over the course of the contract — and agreed to send it to membership for a vote.

Biden took full political credit for that, claiming that he and his administration averted an economically crippling rail strike. Now we know that was BS; all Biden did was kick it down the road past the midterm elections. Four of the twelve unions rejected the deal, specifically on the issue of paid sick leave. Facing political ruin, Biden passed the buck to Congress, which has the legal authority (via the Railway Labor Act, based on Congress’ authority to regulate interstate commerce) to force workers to adopt the negotiated deal whether they like it or not.

Both chambers of Congress will likely pass the bill that imposes Biden’s dumb deal. The House has already passed that bill 290-137 this afternoon. However, House Democrats decided to eat their cake and have it too by offering a second, entirely separate bill that creates seven sick days a year for rail workers on top of the compensation negotiated between arbitrators and both sides. That bill only barely made it out of the House:

A vote to push through a tentative agreement — and thus avert a potentially economy-rattling strike — passed with substantial bipartisan support. 79 Republicans joined 211 Democrats in voting to pass the measure.

The additional measure that would tack on more sick days for workers had much closer margins, with 3 Republicans joining 218 Democrats to pass the resolution.

Paid sick leave, or lack thereof, has emerged as one of the biggest issues among rail workers. Currently, workers have no paid sick days. In the lead up to contract negotiations, workers pushed for 15 paid sick days to be added; they ended up with just one additional personal day, leading many to vote against that agreement. …

But both the tentative agreement and the paid sick leave resolution still need to pass the Senate. If the agreement passed without paid sick leave, “it’s going to make life hard for railroad workers,” Grooters said.

“Without paid time off under what the railroads are trying to do, it just becomes very difficult — and near impossible — to manage your life and exist outside of the railroads.”

That’s a moral argument for negotiations, however, not a legal or economic argument for congressional intervention. I’m actually highly sympathetic to this point; it seems ridiculous that workers have no recourse for immediate acute illness without incurring penalties that eventually can jeopardize employment. That’s especially true in the exit stages of a pandemic which reminded us all of the virtues of staying out of the workplace while symptomatic.

That’s not the whole story, however. While national agreements leave out sick days, local agreements often (but not always) include them, and other benefits apply at the national level:

The PEB had rejected unions’ proposal for 15 days of sick leave nationwide. Sick leave is currently negotiated at the local level, not in national bargaining. The PEB recommended it stay there. Sick leave in the rail industry is different than it is in other industries because of the 24/7 nature of the business, but plenty of sick benefits exist. Depending on local agreements, some workers do get an allotted number of sick days. Others get 26 weeks of partial-income replacement, or 52 weeks of supplemental sickness benefit, which includes a higher rate of partial-income replacement.

Railroads and unions again went to the negotiating table, under the supervision of Secretary of Labor Marty Walsh, and emerged after 20 hours with a deal that included a railroad concession on sick benefits that was celebrated in the Rose Garden at the White House on September 15. President Biden said, “It’s about the right to go to a doctor or stay healthy and make sure you’re able to have the care you can afford. It’s all part of this agreement.” The railroads and leadership of all twelve unions approved.

Even if the sick-days issue required an explicit solution at the national level, and it might, this is a position for which union negotiators could have horse-traded to get. (National Review’s editors point out that unions have had plenty of opportunities to press that point in this and previous contracts, but have chosen to focus on other compensation instead.) The unions could have surrendered some of the extra income in this package, or deferred other concessions, or at the very least refused to send for a vote without adding in some sick days. Instead, they took the compensation offered, which still remains in this deal, and sent it to members with a recommendation to accept it. House Democrats now propose to add more compensation unilaterally, without any participation from the people who will foot the bill for it — the rail companies and services — to satisfy the workers who didn’t follow their own leadership.

That’s morally unfair, and economically foolish. This will raise costs even higher on distribution of goods in the US than the original deal did. Even worse, the recourse to Congress to impose more concessions than even unions agreed to take creates a moral hazard that will end up forcing Congress to resolve more and more of these contract disputes, and making campaign contributions the primary criterion for labor-management policy (even more than they are at the moment).

The counter-argument to this is … what, exactly? That union leadership and negotiators are too incompetent to bargain for their own benefit? Forcing workers to take the deal that their unions negotiated and they later rejected may be unfair, but it’s far worse to change the deal to favor one side and impose that on the other side rather than impose the deal both sides agreed upon in arbitration.

By splitting the bill, House Democrats neatly avoided any responsibility for imposing the negotiated deal while at the same time also avoiding any blame for a strike. The odds of both bills passing the Senate look slim, John Cornyn later said, although he’s pretty sure the bailout of Biden will make it through:

Sen. Cornyn says he’ll oppose the paid leave provision on railroads and predicts it will get some Republicans but not 10

“I'm not going to support it because I don't want to set a precedent for rewriting collective bargaining agreements”

— Burgess Everett (@burgessev) November 30, 2022

Politically, House Democrats took the clever route. The Senate should stick to the economic, legal, and moral principles and do as Cornyn advises. The Railway Labor Act gives Congress the authority to impose an agreement, not to act as negotiators for workers or management, which is what the second bill clearly does. If unions want to settle sick days in the national contract the next time, let them make that their priority.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member