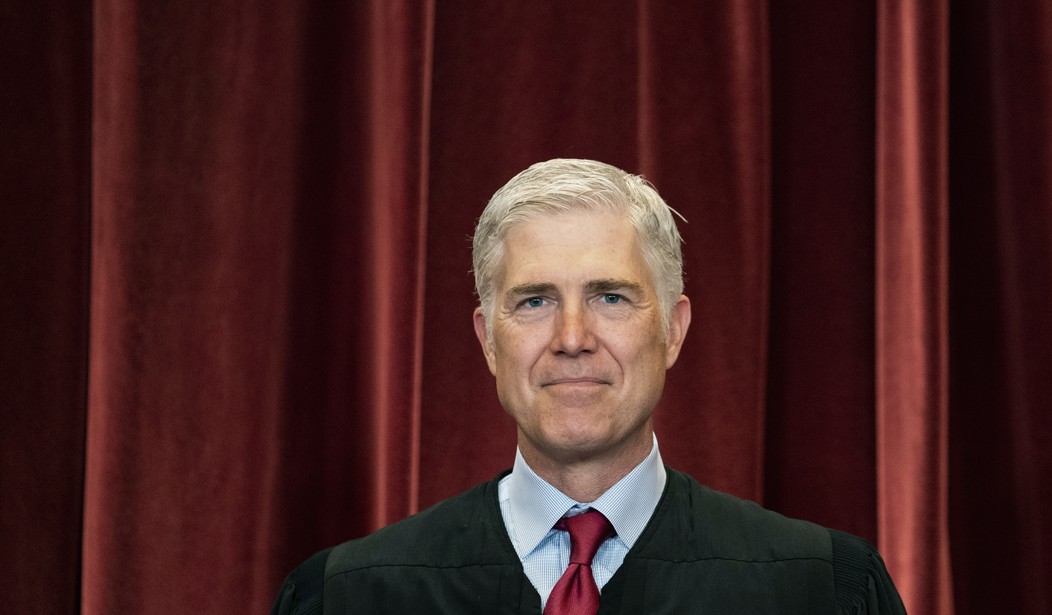

Does a coach offend the Establishment Clause by kneeling in prayer on a school football field? In a 6-3 ruling authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch in Kennedy v Bremerton, the answer is no. Coach Joseph Kennedy got fired from Bremerton School District for offering a “personal prayer” at the end of his high-school team’s football games. Gorsuch and the majority — joined by Roberts in this case — ruled that the school district had violated both the Free Speech and Free Exercise clauses of the First Amendment.

Furthermore, Gorsuch wrote, they showed a remarkable intolerance in the name of tolerance:

Joseph Kennedy lost his job as a high school football coach because he knelt at midfield after games to offer a quiet prayer of thanks. Mr. Kennedy prayed during a period when school employees were free to speak with a friend, call for a reservation at a restaurant, check email, or attend to other personal matters. He offered his prayers quietly while his students were otherwise occupied. Still, the Bremerton School District disciplined him anyway. It did so because it thought anything less could lead a reasonable observer to conclude (mistakenly) that it endorsed Mr. Kennedy’s religious beliefs. That reasoning was misguided. Both the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment protect expressions like Mr. Kennedy’s. Nor does a proper understanding of the Amendment’s Establishment Clause require the government to single out private religious speech for special disfavor. The Constitution and the best of our traditions counsel mutual respect and tolerance, not censorship and suppression, for religious and nonreligious views alike. …

This case involves three Clauses of the First Amendment. As a threshold matter, the Court today proceeds from two mistaken understandings of the way the protections these Clauses embody interact.

First, the Court describes the Free Exercise and Free Speech Clauses as “work[ing] in tandem” to “provid[e] overlapping protection for expressive religious activities,” leaving religious speech “doubly protect[ed].” Ante, at 11. This narrative noticeably (and improperly) sets the Establishment Clause to the side. The Court is correct that certain expressive religious activities may fall within the ambit of both the Free Speech Clause and the Free Exercise Clause, but “the First Amendment protects speech and religion by quite different mechanisms.” Lee, 505 U. S., at 591. The First Amendment protects speech “by ensuring its full expression even when the government participates.” Ibid. Its “method for protecting freedom of worship and freedom of conscience in religious matters is quite the reverse,” however, based on the understanding that “the government is not a prime participant” in “religious debate or expression,” whereas government is the “object of some of our most important speech.” Ibid. Thus, as this Court has explained, while the Free Speech Clause has “close parallels in the speech provisions of the First Amendment,” the First Amendment’s protections for religion diverge from those for speech because of the Establishment Clause, which provides a “specific prohibition on forms of state intervention in religious affairs with no precise counterpart in the speech provisions.” Ibid. Therefore, while our Constitution “counsel[s] mutual respect and tolerance,” the Constitution’s vision of how to achieve this end does in fact involve some “singl[ing] out” of religious speech by the government. Ante, at 1. This is consistent with “the lesson of history that was and is the inspiration for the Establishment Clause, the lesson that in the hands of government what might begin as a tolerant expression of religious views may end in a policy to indoctrinate and coerce.” Lee, 505 U. S., at 591–592.

Second, the Court contends that the lower courts erred by introducing a false tension between the Free Exercise and Establishment Clauses. See ante, at 20–21. The Court, however, has long recognized that these two Clauses, while “express[ing] complementary values,” “often exert conflicting pressures.” Cutter, 544 U. S., at 719. See also Locke v. Davey, 540 U. S. 712, 718 (2004) (describing the Clauses as “frequently in tension”). The “absolute terms” of the two Clauses mean that they “tend to clash” if “expanded to a logical extreme.” Walz, 397 U. S., at 668–669.

The Court inaccurately implies that the courts below relied upon a rule that the Establishment Clause must always “prevail” over the Free Exercise Clause. Ante, at 20. In focusing almost exclusively on Kennedy’s free exercise claim, however, and declining to recognize the conflicting rights at issue, the Court substitutes one supposed blanket rule for another. The proper response where tension arises between the two Clauses is not to ignore it, which effectively silently elevates one party’s right above others. The proper response is to identify the tension and balance the interests based on a careful analysis of “whether [the] particular acts in question are intended to establish or interfere with religious beliefs and practices or have the effect of doing so.” Walz, 397 U. S., at 669. As discussed above, that inquiry leads to the conclusion that permitting Kennedy’s desired religious practice at the time and place of his choosing, without regard to the legitimate needs of his employer, violates the Establishment Clause in the particular context at issue here.

This explicitly rejects the Lemon test for Establishment Clause jurisprudence, a 1971 case that made the Establishment Clause a higher priority than free speech and free religious expression. Gorsuch writes that the Supreme Court had long before tacitly rejected the Lemon construct, and now says that the court will explicitly instruct against it:

What the District and the Ninth Circuit overlooked, however, is that the “shortcomings” associated with this “ambitiou[s],” abstract, and ahistorical approach to the Establishment Clause became so “apparent” that this Court long ago abandoned Lemon and its endorsement test offshoot. American Legion, 588 U. S., at ___–___ (plurality opinion) (slip op., at 12–13); see also Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U. S. 565, 575–577 (2014). The Court has explained that these tests “invited chaos” in lower courts, led to “differing results” in materially identical cases, and created a “minefield” for legislators. Pinette, 515 U. S., at 768–769, n. 3 (plurality opinion) (emphasis deleted). This Court has since made plain, too, that the Establishment Clause does not include anything like a “modified heckler’s veto, in which . . . religious activity can be proscribed” based on “‘perceptions’” or “‘discomfort.’” Good News Club v. Milford Central School, 533 U. S. 98, 119 (2001) (emphasis deleted). An Establishment Clause violation does not automatically follow whenever a public school or other government entity “fail[s] to censor” private religious speech. Board of Ed. of Westside Community Schools (Dist. 66) v. Mergens, 496 U. S. 226, 250 (1990) (plurality opinion). Nor does the Clause “compel the government to purge from the public sphere” anything an objective observer could reasonably infer endorses or “partakes of the religious.” Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U. S. 677, 699 (2005) (BREYER, J., concurring in judgment). In fact, just this Term the Court unanimously rejected a city’s attempt to censor religious speech based on Lemon and the endorsement test. See Shurtleff, 596 U. S., at ___–___ (slip op., at 1–2); id., at ___ (ALITO, J., concurring in judgment) (slip op., at 1); id., at ___, ___–___ (opinion of GORSUCH, J.) (slip op., at 1, 4–5).4

In place of Lemon and the endorsement test, this Court has instructed that the Establishment Clause must be interpreted by “‘reference to historical practices and understandings.’” Town of Greece, 572 U. S., at 576; see also American Legion, 588 U. S., at ___ (plurality opinion) (slip op., at 25). “‘[T]he line’” that courts and governments “must draw between the permissible and the impermissible” has to “‘accor[d] with history and faithfully reflec[t] the understanding of the Founding Fathers.’” Town of Greece, 572 U. S., at 577 (quoting School Dist. of Abington Township v. Schempp, 374 U. S. 203, 294 (1963) (Brennan, J., concurring)). An analysis focused on original meaning and history, this Court has stressed, has long represented the rule rather than some “‘exception’” within the “Court’s Establishment Clause jurisprudence.” 572 U. S., at 575; see American Legion, 588 U. S., at ___ (plurality opinion) (slip op., at 25); Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U. S. 488, 490 (1961) (analyzing certain historical elements of religious establishments); McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U. S. 420, 437–440 (1961) (analyzing Sunday closing laws by looking to their “place . . . in the First Amendment’s history”); Walz v. Tax Comm’n of City of New York, 397 U. S. 664, 680 (1970) (analyzing the “history and uninterrupted practice” of church tax exemptions). The District and the Ninth Circuit erred by failing to heed this guidance.

The dissent from Justice Sonia Sotomayor attempts to resurrect the Lemon test, to no avail:

Despite all of this authority, the Court claims that it “long ago abandoned” both the “endorsement test” and this Court’s decision in Lemon 403 U. S. 602. Ante, at 22. The Court chiefly cites the plurality opinion in American Legion v. American Humanist Assn., 588 U. S. ___ (2019) to support this contention. That plurality opinion, to be sure, criticized Lemon’s effort at establishing a “grand unified theory of the Establishment Clause” as poorly suited to the broad “array” of diverse establishment claims. 588 U. S., at ___, ___ (slip op., at 13, 24). All the Court in American Legion ultimately held, however, was that application of the Lemon test to “longstanding monuments, symbols, and practices” was ill-advised for reasons specific to those contexts. 588 U. S., at ___ (slip op., at 16); see also id., at ___– ___ (slip op., at 16–21) (discussing at some length why the Lemon test was a poor fit for those circumstances). The only categorical rejection of Lemon in American Legion appeared in separate writings.

Lemon’s dead now, however. In its place is a balancing test that actually makes sense — whether a religious exercise in connection with a public entity is profound enough to tip over into a government endorsement rather than a function of personal free speech and/or religious expression. That balancing test, likely to be called a Kennedy test at some point, treats all of these constitutional provisions equally rather than preference the government positions under the Establishment Clause ahead of the First Amendment. It would be an actual example of tolerance in its true meaning. And that hews much closer to the original intent of the Establishment Clause, which wasn’t to prohibit religious expression in public but to prevent governments from creating an official religion.

It’s a wise decision. I may have more on this as events break from the Supreme Court this morning.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member