Is economic pessimism really mostly about “partisanship and prices,” as the Washington Post’s Philip Bump argued late yesterday? Or is it a rational reflection of an economic reality? The World Bank warned yesterday that the global economy has already turned toward a replay of 1970s-era stagflation, with growth estimates chopped by more than a full point from its earlier forecast.

That’s due in part to the war in Ukraine, but that’s only part of the reason:

The global economy may be headed for years of weak growth and rising prices, a toxic combination that will test the stability of dozens of countries still struggling to rebound from the pandemic, the World Bank warned Tuesday.

Not since the 1970s — when twin oil shocks sapped growth and lifted prices, giving rise to the malady known as “stagflation” — has the global economy faced such a challenge.

The bank slashed its annual global growth forecast to 2.9 percent from January’s 4.1 percent and said that “subdued growth will likely persist throughout the decade because of weak investment in most of the world.”

Or maybe we should call it That 40s Show instead. The World Bank projects that the post-COVID period could be the worst rebound since the end of World War II:

This will be the sharpest slump after an initial post-recession rebound that the global economy has suffered in more than 80 years, the bank said. And the situation could get even worse if the Ukraine war fractures global trade and financial networks or soaring food prices spark social unrest in importing countries.

“The risk from stagflation is considerable with potentially destabilizing consequences for low- and middle-income economies,” said David Malpass, president of the multilateral development institution in Washington. “ … There’s a severe risk of malnutrition and of deepening hunger and even of famine in some areas.”

That comparison may be more analogous. The global stagnation at the end of WWII came in large part because so much national wealth had been destroyed in Europe and the Pacific Rim. The US avoided much of that destruction, and even then we suffered through an economic downturn in the immediate aftermath of the war. Without capital to invest, Europe entered into a stasis of poverty and famine, until the US pulled together its Marshall Plan after dealing with our war debt to revitalize the continent.

The lack of real capital then parallels our situation now. In the 1970s, we had oil shocks, asset bubbles, and over-regulation that created the stagflation maelstrom, but we didn’t have a significant amount of national debt in relation to GDP. The debt-to-GDP ratio remained in the low 30% range all decade long, giving the US lots of flexibility for budgeting and investment.

Now, however, we’re back to oil shocks, asset bubbles, and over-regulation impeding economic growth, but our debt-to-GDP ratio is now 124%. That’s higher than it was during World War II in any one year; 114% in 1945 was the wartime high, and it got to 119% in 1946 as the US economy went into recession. We no longer have any flexibility for capital investment to deal with the strategic conditions of the present day, especially while we refuse to extract and refine the oil we can access.

As for Bump’s argument, pessimism looks like the correct rational reaction to this set of circumstances, but YMMV:

By many measures, the American economy is doing well. Unemployment is near record lows and employment near highs. Competition for workers has helped push wages higher. Drop an American from 2009 or mid-2020 into the 2022 job market and they’d presumably be thrilled.

But those higher wages are less useful when gas prices are at a record high. Earning more each week is dampened by paying more for food and other products, particularly things that are downstream from fuel costs.

It is no wonder, then, that polling from YouGov conducted for The Economist found last month that 58 percent of Americans think the economy is getting worse. …

The effect of the pandemic about three-quarters of the way through Donald Trump’s term in office is obvious; confidence in the economy plummeted. It recovered for a bit before dropping off again. Then, soon after President Biden took office — and as the pandemic seemed to be receding for good — optimism returned. Until it didn’t.

An inextricable part of this is partisanship. If we separate out the parties in the YouGov polling, you can see how much views of the economy depend on party. During Obama’s presidency, Democrats were pretty confident in the economy while Republicans were extremely pessimistic. Then Trump took office and positions quickly flipped.

Oddly, the latest longitudinal poll from the WSJ on economic outlook doesn’t get a mention. In a poll where Democrats and Democrat-leaning independents make up 48% of the sample, 83% of respondents describe the economy as “poor” (55%) or “not so good.” Only 27% of respondents see hope of improving their standard of living over the next few years, down 19 points from the previous year. That certainly doesn’t look like partisanship driving the results. And what’s more, it reflects the reality of a jobs market that, contra Bump, has still not yet fully recovered from the pandemic destruction in April 2020 and where buying power has steadily eroded even for those who are working at the moment.

As the Associated Press and Bump’s colleague Heather Long pointed out over the past few days, the economy is only working for the wealthy at the moment. That was another feature of the 1970s stagflation cycle, and the stratification isn’t just on prices but rent. And again as Bump’s own newspaper points out, the poorer are getting hammered the hardest there, too:

Surging home prices and rents are cascading down to the country’s mobile home parks, where heightened demand, low supply and an increase in corporate owners is driving up monthly costs for low-income residents with few alternatives. At the same time, private-equity firms and developers are often circling nearby, looking to buy up such properties and turn them into more lucrative ventures, including timeshare resorts, wedding venues and condominiums.

Mobile homes have long been one of the country’s most affordable housing options, particularly for families who do not receive government aid. About 20 million Americans live in manufactured homes, which make up about 6 percent of U.S. residences, according to federal data. Some experts suggest those numbers could soon rise as more people are priced out of traditional houses and apartments.

Mobile homes prices range from less than $25,000 in Nebraska, Iowa and Ohio, to more than $125,000 in Washington state. Overall, they tend to be three to five times cheaper than traditional single-family homes, according to an analysis of census data by LendingTree.

But rising demand for affordable housing has put particular pressure on the market. Nationally, the average sales price of manufactured homes has risen nearly 50 percent during the pandemic, from $82,900 to $123,200, census data shows. Meanwhile, average new home prices rose 22 percent in that period, according to government figures.

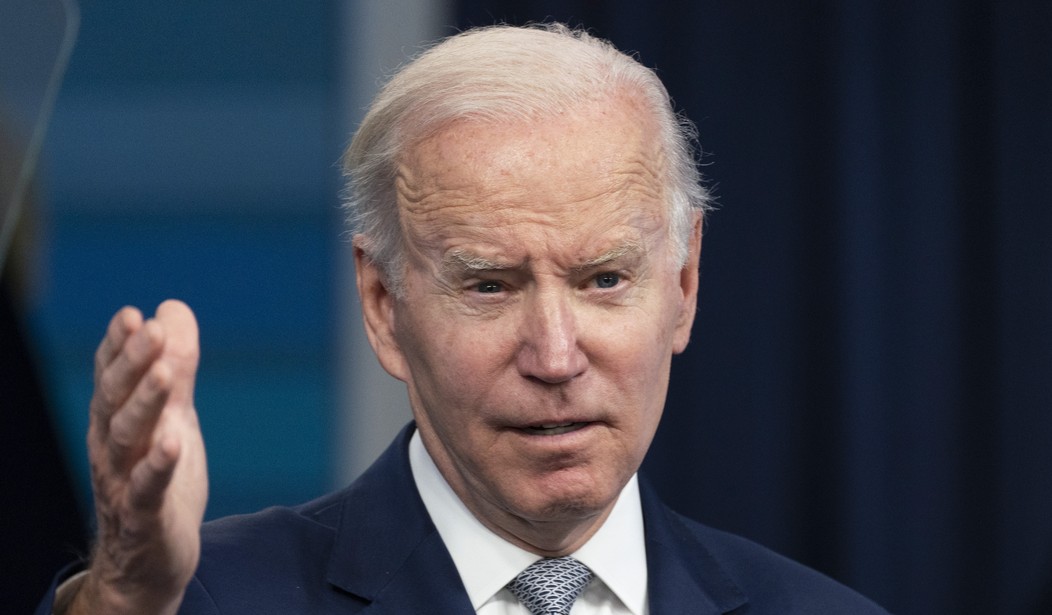

Pessimism isn’t partisan among the working- and middle-class households of America. It’s the daily reality of Joe Biden’s economy.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member