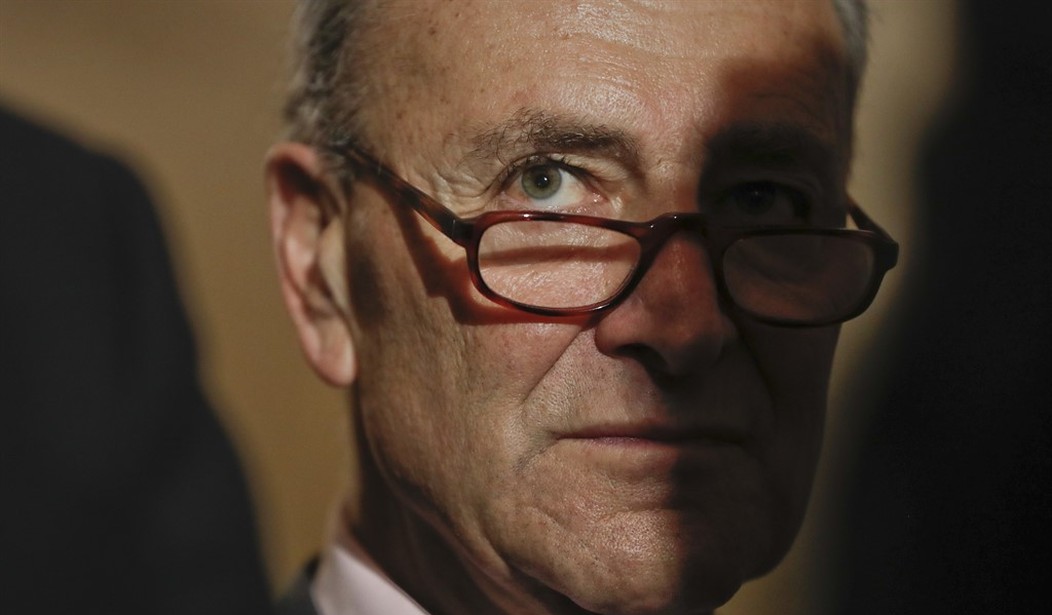

Senate Democrats, led by Chuck Schumer, have begun demanding a special counsel to open an independent investigation into the allegations of Russian interference in the 2016 election. Schumer took his case to the Senate floor yesterday even as the White House explanation for James Comey’s firing as FBI director began to unravel and dozens of leaks put the onus for it squarely on Donald Trump’s frustration over the attention paid to the Russia probe. The chain of events show that an investigation within the Trump administration would be hopelessly compromised, Schumer alleges:

Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer on Wednesday called on the Department of Justice to appoint a special prosecutor to take over the FBI investigation into possible collusion between Russia and the Trump campaign following President Donald Trump’s decision to fire FBI Director James Comey.

“If there was ever a time when circumstances warranted a special prosecutor, it is right now,” Schumer said in remarks on the Senate floor. …

“Mr. Rosenstein already expressed concern that Director Comey damaged the integrity of the FBI. The attorney general has already had to recuse himself from the investigation for being too close to the president,” Schumer said. “If Mr. Rosenstein is true to his word, that he believes this investigation must be, quote, ‘fair, free, thorough and politically independent,’ if he believes as I do that the American people must be able to have faith in the impartiality of this investigation, he must appoint a special prosecutor and get his investigation out of the hands of the FBI and far away from the heavy hand of this administration.”

Why stop at one, though, if that’s the bar for appointing a special counsel (the more accurate term)? Since we’re using Rosenstein and Comey as authorities on this question, then let’s make sure we have remedied all of the political interference into criminal probes of high-ranking officials. As I argue in my column for The Fiscal Times, we should start by appointing a special counsel to review the Hillary Clinton investigation and particularly whether political interference corrupted the outcome. After all, both Comey and Rosenstein have either implied or directly stated that it was a factor in ending law-enforcement efforts:

When The New York Times broke the news about Hillary Clinton’s secret e-mail server in February 2015, it immediately raised issues about conflicts of interest with the current administration. Clinton was hiding those e-mails while serving as Barack Obama’s Secretary of State and was about to become his party’s frontrunner to replace him in the White House. Calls started early for a special counsel to conduct the investigation, but Obama and Lynch refused to accommodate them.

Even after the news of Lynch’s tarmac meeting with Bill Clinton in Phoenix broke, Lynch not only dismissed calls for a special counsel, she refused to fully recuse herself from any decision to prosecute. Lynch promised to accept whatever recommendation came from the FBI – a point which partially rebuts Rosenstein’s conclusions – but left herself in charge of the overall decision. A spokeswoman for the Department of Justice made that clear immediately afterward. “She’s the head of the department,” Melanie Newman noted, “and with that comes ultimate responsibility for any decision.”

At that point, a special prosecutor should have been appointed to relieve the political appointees of any input into the potential pursuit of criminal charges. Given Comey’s description of the findings of that investigation – especially with the grossly negligent handling of highly classified material by Clinton and her team – there is good reason for a special counsel to review the case again, independent of both the Obama and Trump administrations. Had a special counsel been appointed at the time, the career of a dedicated but perhaps misguided public servant might not have been ended this week.

The same issues pertain to the investigation into alleged Russian tampering with the 2016 election. Those allegations potentially involve people within the highest levels of government, and the expectation that politics can remain removed from these considerations has already been eclipsed. Firing the man in charge of those investigations while they remain in process, no matter how well-deserved the action may or may not be, raises the potential of political interference into law enforcement.

Generally speaking, appointing a special counsel is the last option. It creates a significant issue with accountability, and in almost every instance the investigations veer off into irrelevant tangents when the central issue cannot be resolved. That’s what happened with Ken Starr’s Whitewater probe, and with Patrick Fitzgerald’s investigation into the Valerie Plame leak. Jonathan Tobin makes a good argument against appointing special counsels in any case:

Since no administration can be trusted to investigate itself, it stands to reason that what is needed is someone who can operate independently of the White House and even independently from the office of the attorney general. That makes good sense. But the well-established dynamic of special prosecutors is that instead of focusing on providing answers about the specific controversy that brought them to life, they quickly become attached to the extraordinary power they’ve been given.

That means that their investigation becomes not a means to the end for which they were purposed, but an end in itself. Few of those put in charge of what generally amounts to unlimited budgets and the full force of the federal government, without any effective check on their decisions, have ever been content to leave office without indicting someone for something, even if it is entirely unrelated to their original brief.

These examples show that special prosecutors are rarely interested in giving the public the information that their efforts were supposed to produce. That’s why the Obama administration steadfastly refused to appoint a single such prosecutor during their eight years in office, even though there was no shortage of scandals: the IRS’s misuse of its power to harm conservative groups; the Fast and Furious gun-walking affair involving the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives; the massive fraud and incompetence at Veterans Affairs hospitals; the spying on James Rosen and other journalists; and, of course, Hillary Clinton’s e-mails. Obama knew that setting a prosecutor with unlimited power loose on his government would ultimately create, fairly or unfairly, some Democratic casualties, and he wanted no part of it.

Tobin favors appointing an independent panel, presumably with subpoena power, along the lines of the 9/11 Commission. A balanced commission might do better at staying disciplined to the point at hand, but it’s not clear that they’d have as much impact either. On top of that, that kind of commission could result in torpedoing prosecutions where they might otherwise be warranted, which is a risk with Congressional investigations as well. Tobin’s higher calling here is fact-finding, which might not necessarily be the right mission for either of these investigations.

Don’t expect special counsels to get appointed soon, however. The nomination of a new FBI director might moot the issue if he or she is well-respected and independent enough to lead a credible investigation. This CBS News report from yesterday covers the reasons for skepticism pretty well.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member