There is a lot of talk about the dangers of the COVID vaccines these days, some of which is pure speculation and some of which is based upon solid facts and science.

Let me focus on the latter, because speculation sheds a lot of heat but not any light.

The Wall Street Journal has printed a story on its Editorial page that should cause a stir: recent peer reviewed studies indicate that the policy of frequently boosting vaccinated people against new COVID variants is speeding up the mutation of the virus and actually encouraging the spread of the virus rather than slowing it down.

Drawing on studies printed in Nature and the New England Journal of Medicine, Allysia Finley’s article questions the wisdom of the constant drive to develop new vaccine boosters to combat the evolving strains of COVID-19. If I understand the argument correctly, our efforts are creating a situation similar to antibiotic resistant bacteria–we are teaching the virus how to evade the weapons we are using to combat the spread of the virus.

Public-health experts are sounding the alarm about a new Omicron variant dubbed XBB that is rapidly spreading across the Northeast U.S. Some studies suggest it is as different from the original Covid strain from Wuhan as the 2003 SARS virus. Should Americans be worried?

It isn’t clear that XBB is any more lethal than other variants, but its mutations enable it to evade antibodies from prior infection and vaccines as well as existing monoclonal antibody treatments. Growing evidence also suggests that repeated vaccinations may make people more susceptible to XBB and could be fueling the virus’s rapid evolution.

It is that second part–that people who have been vaccinated and boosted multiple times are more susceptible to infection–that is particularly worrying.

We use antibiotics despite the danger of creating resistant bacteria because doing so saves lives. However, we don’t use antibiotics constantly because that teaches the sneaky little bugs how to evade them without providing a life-saving benefit. We use them when necessary, and sparingly.

However we are not doing that with the COVID vaccines, and that may be a huge mistake. Instead of focusing our immunity boosting efforts on people most in danger, we are pursuing a strategy of universal vaccination regardless of risk. That accelerates the mutation process, essentially wasting the temporary advantage we have against the virus (a vaccine that helps) in a vain effort to stop the virus cold.

We know stopping the virus is impossible. Experience tells us this. So is our current strategy actually making things worse?

Prior to Omicron’s emergence in November 2021, there were only four variants of concern: Alpha, Beta, Delta and Gamma. Only Alpha and Delta caused surges of infections globally. But Omicron has begotten numerous descendents, many of which have popped up in different regions of the world curiously bearing some of the same mutations.

“Such rapid and simultaneous emergence of multiple variants with enormous growth advantages is unprecedented,” a Dec. 19 study in the journal Nature notes. Under selective evolutionary pressures, the virus appears to have developed mutations that enable it to transmit more easily and escape antibodies elicited by vaccines and prior infection.

The same study posits that immune imprinting may be contributing to the viral evolution. Vaccines do a good job of training the immune system to remember and knock out the original Wuhan variant. But when new and markedly different strains come along, the immune system responds less effectively.

Bivalent vaccines that target the Wuhan and BA.5 variants (or breakthrough infections with the latter) prompt the immune system to produce antibodies that target viral regions the two strains have in common. In Darwinian terms, mutations that allow the virus to evade common antibodies win out—they make it “fitter.”

XBB has evolved to elude antibodies induced by the vaccines and breakthrough infections. Hence, the Nature study suggests, “current herd immunity and BA.5 vaccine boosters may not efficiently prevent the infection of Omicron convergent variants.”

Imagine, if you will, a scenario where we focused on protecting the most vulnerable through vaccination and skipped the majority of people. The strains in circulation would indeed have their way with more people, but those people would be at little risk of developing serious complications from the virus. There would be no “incentive” for viral mutations because the circulating strain was “fit” enough. The vaccines would protect the most vulnerable still, but evolve more slowly, extending the useful life of the vaccine.

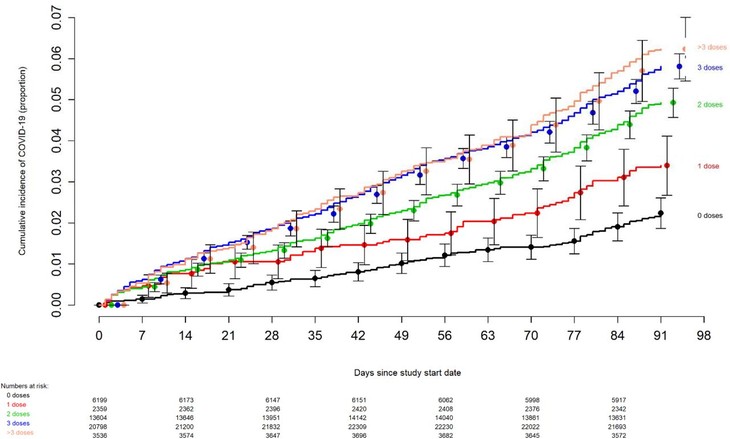

A Cleveland Clinic study found something even more troubling: susceptibility to COVID infection appears to go up the more boosters you get, confounding expectations:

Notably, workers who had received more doses were at higher risk of getting sick. Those who received three more doses were 3.4 times as likely to get infected as the unvaccinated, while those who received two were only 2.6 times as likely.

“This is not the only study to find a possible association with more prior vaccine doses and higher risk of COVID-19,” the authors noted. “We still have a lot to learn about protection from COVID-19 vaccination, and in addition to a vaccine’s effectiveness it is important to examine whether multiple vaccine doses given over time may not be having the beneficial effect that is generally assumed.”

Two years ago, vaccines were helpful in reducing severe illness, particularly among the elderly and those with health risks like diabetes and obesity. But experts refuse to concede that boosters have yielded diminishing benefits and may even have made individuals and the population as a whole more vulnerable to new variants like XBB.

The correlation between getting infected with COVID-19 during the Cleveland Clinic study and vaccination is startling–the more vaccinations a person had, the higher the likelihood of getting a case of COVID. This is a result that is both the opposite of what would be expected and of what would be desired. Despite this, the authors concluded that the bivalent booster was about 30% effective, but with huge caveats–ones that suggest the current vaccine strategy is a big mistake.

Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for hazard ratios for the variables included in the unadjusted and adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression models are shown in Table 2. The calculated overall vaccine effectiveness from the model was 30% (95% C.I., 20% – 39%).

Table 2.Unadjusted and Adjusted Associations with Time to COVID-19The multivariable analyses also found that, the more recent the last prior COVID-19 episode was the lower the risk of COVID-19, and that the greater the number of vaccine doses previously received the higher the risk of COVID-19.

The authors are pretty clear in their discussion of the results that the current vaccine strategy has to be reevaluated for obvious reasons. If the goal is to stop the spread of the virus the opposite is actually happening. The more vaccinated you are, the more likely you are to get COVID.

The evolution of the SARS-CoV-2 virus necessitates a more nuanced approach to assessing the potential impact of vaccination than when the original vaccines were developed. Additional factors beyond vaccine effectiveness need to be considered. The association of increased risk of COVID-19 with higher numbers of prior vaccine doses in our study, was unexpected. … those who received fewer than 3 doses (>45% of individuals in the study) were not those ineligible to receive the vaccine, but those who chose not to follow the CDC’s recommendations on remaining updated with COVID-19 vaccination, and one could reasonably expect these individuals to have been more likely to have exhibited higher risk-taking behavior. Despite this, their risk of acquiring COVID-19 was lower than those who received a larger number of prior vaccine doses. This is not the only study to find a possible association with more prior vaccine doses and higher risk of COVID-19. A large study found that those who had an Omicron variant infection after previously receiving three doses of vaccine had a higher risk of reinfection than those who had an Omicron variant infection after previously receiving two doses of vaccine [21]. Another study found that receipt of two or three doses of a mRNA vaccine following prior COVID-19 was associated with a higher risk of reinfection than receipt of a single dose [7]. We still have a lot to learn about protection from COVID-19 vaccination, and in addition to a vaccine’s effectiveness it is important to examine whether multiple vaccine doses given over time may not be having the beneficial effect that is generally assumed.

That last sentence is pretty much a disaster for the CDC.

With all the arguments going on about potential vaccine side effects and the potential dangers it is easy to ignore the lessons from this study: even if the vaccines are perfectly, 100% safe as a saline drip, it turns out that they are not having the intended effect. They may in fact be doing the opposite of what is intended.

Sounds like a government program to me. Ineffective and potentially harmful.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member