If you’re not sure why Mattis needs a waiver to lead the Pentagon, read this for quickie background. Congress passed a law years ago mandating that any veteran tapped to lead the Defense department had to have been retired from the service for a certain number of years. That was a concession to the American ideal of civilian control of the military: You don’t want a service member at the top of the military hierarchy. That law was waived once before for George Marshall but it hasn’t been tested since. Currently it requires a retirement period of seven years; Mattis has only been retired for four, which means he’s ineligible for the post — unless Congress passes a bill granting him a waiver too.

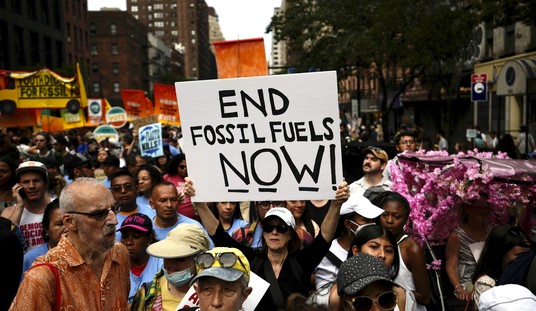

And note well: Because this would be an amendment to an existing law, not a simple matter of confirmation, Democrats do have the power to filibuster it. They’ll have 48 seats in the Senate in January; all they need are 41 votes to block the waiver and stop Mattis. Sounds like Kirsten Gillibrand’s ready for a fight.

Gillibrand’s early opposition to the waiver came less than an hour after Trump announced he would tap Mattis for the Pentagon. The popular commander, nicknamed “Mad Dog,” is still expected to become the first defense secretary nominee in more than 60 years to win the congressional waiver that’s necessary to install him as the military’s civilian leader given his recent service in uniform.

“While I deeply respect General Mattis’s service, I will oppose a waiver,” Gillibrand said in a statement. “Civilian control of our military is a fundamental principle of American democracy, and I will not vote for an exception to this rule.”

McConnell should be able to flip eight Democrats considering how highly respected Mattis is. (The only Republican I’d imagine he might lose is Rand Paul, for the same reason Gillibrand gave.) The list of red- and purple-state Dems whose seats are up in 2018 runs on and on — Tester, McCaskill, Donnelly, Heitkamp, Manchin, Baldwin, Casey, Brown, Nelson. If all of them flipped, Mattis would have enough votes to beat a filibuster on the waiver even if Paul voted no. The suspense has to do, really, with how much liberal activists will make a point of trying to stop him. They’re looking for a way to deal Trump an early defeat but they’re limited in what they can do on appointments after Harry Reid foolishly nuked the filibuster for presidential nominees a few years ago. The waiver issue gives them an opening. If they make a stink about Mattis, some of those red-state Democrats I named will get nervous about alienating their base and end up voting no on a waiver. Gillibrand’s statement, I assume, is a cheap way of showing leadership to the left early in the Trump era, with her eye on 2020 or 2024.

But wait. Even if McConnell can’t find 60 votes for a waiver, there’s another way Trump and Mattis can overcome Democratic resistance. Shannen Coffin asks a good question: Is the law that imposes a mandatory retirement term for veterans before they can lead the Defense department constitutional?

This statutory limitation on the president’s power to appoint officers of his choosing is almost certainly unconstitutional. The constitution vests the President with the sole authority to nominate executive officers of his choosing. The only constitutional limitation is the incompatability clause – which prevents a member of Congress from serving in any “Office of the United States.”

Congress has no role in deciding whom the president can nominate. Congress does have a role in the appointment of those officers, but that is limited to the Senate’s “advise and consent” role. In both the nomination and appointment process, the ultimate power lies with the President. Congress cannot limit who the president chooses to appoint as an executive officer. The Senate can withhold consent, but that is as far as they can go in preventing the president’s appointment.

So can the legislation be viewed as a condition of the Senate’s consent? That’s also doubtful – or better yet, just plain wrong. The House can have no role in how the Senate exercises its constitutional authority, and even more, no individual Senator can be beholden to a legislative whim of prior Congresses in deciding how to exercise the advice and consent role. So legislation that directs the Senate how to vote on a confirmation would be equally problematic.

Imagine that McConnell had 60 votes to change the law by granting a waiver to Mattis but the House refused to go along and blocked the legislation. The House would, in essence, be vetoing a presidential nominee even though it’s supposed to have no role in the confirmation process under the Constitution. If the Senate believes that Mattis is still too fresh from the service to comfortably fill what’s supposed to be a civilian role, it can and should take that into consideration in deciding whether to confirm him. If it concludes that that concern, while valid, isn’t disqualifying in his particular case, then it should be free per its “advise and consent” power to make that judgment too — except that it isn’t because of the law regarding a certain number of years of retirement by military officers. That being so, a court might very well strike down the law as an infringement on the Senate’s confirmation power. We may get to find out: If Schumer manages to filibuster the GOP’s attempt to pass a waiver for Mattis, McConnell might turn around, hold a floor vote to confirm Mattis anyway, and then dare Schumer to sue Mattis to block his appointment in order to test whether the president’s power in choosing nominees and the Senate’s power of “advise and consent” can be restricted by law.

Which, actually, is another reason to believe there’ll be no filibuster. Knowing that he’d probably lose that court battle, Schumer might decide that it’s not worth alienating voters by trying to block a popular military figure like Mattis when the attempt’s almost sure to fail one way or the other.

This dispute is a neat reminder, though, that the only thing protecting some norms of American government is the good judgment and civic-mindedness of the governors themselves. The reason we haven’t had a steady stream of generals in charge of the Defense department isn’t because there’s a statute on the books that ties the president’s hands, it’s because American presidents have shared the belief that civilian control of the military in a democracy is a good thing and made their appointments accordingly. Trump might not share that belief as strongly; if the public wants to punish him for it, they’ll have a chance in 2020. Ironically, though, I think the fact that Trump is more of a black box when it comes to traditional norms (ahem) is part of the case for making an exception for Mattis and confirming him at Defense. He’s a scholar and a patriot; he’s not a yes-man of the sort that might worry you as Trump’s right-hand man at the Pentagon. Like I said in last night’s post, I think he’ll be a good influence on the commander-in-chief. That’s much more important than whether he’s been retired for seven years or only four.

Update: One more reason to think a Dem filibuster of Mattis won’t come off.

Dems I've talked to in last 24 hours seem more comfortable with Mattis pick than anything Trump has done so far.

— Glenn Thrush (@GlennThrush) December 2, 2016

Join the conversation as a VIP Member