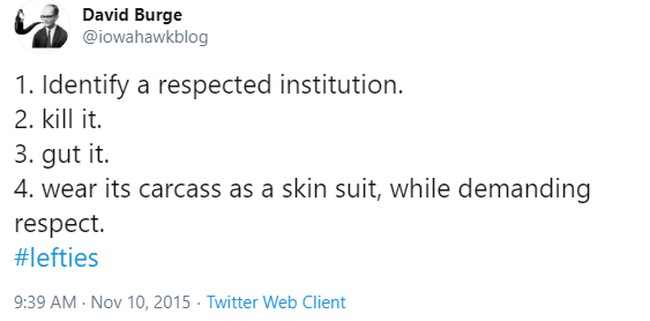

Scientific American is a zombie. Like the walking dead it still moves and appears something like what it was, but the abilities to think and use reason have fled.

I have written several times about what a disaster Scientific American has become, and this article in City Journal fleshes things out, provides some historical context, and is well worth reading.

The collapse of @sciam under editor @laurahelmuth in a morass of partisan anti-science has been sad to watch. I used to love the magazine when I was younger. Autopsy by James Meigs in @CityJournal.https://t.co/BJ5MXK9Xjc

— Jay Bhattacharya (@DrJBhattacharya) May 6, 2024

James Meigs' analysis puts some meat on the bones regarding how the magazine zombified: it caught the mind virus that we call "woke." Rather than being a highbrow popularizer of scientific writing, it became a highbrow publisher of chanting points that would filter down into the educated elite, validating what the blue-haired harpies chanted on our streets and classrooms.

Michael Shermer got his first clue that things were changing at Scientific American in late 2018. The author had been writing his “Skeptic” column for the magazine since 2001. His monthly essays, aimed at an audience of both scientists and laymen, championed the scientific method, defended the need for evidence-based debate, and explored how cognitive and ideological biases can derail the search for truth. Shermer’s role models included two twentieth-century thinkers who, like him, relished explaining science to the public: Carl Sagan, the ebullient astronomer and TV commentator; and evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould, who wrote a popular monthly column in Natural History magazine for 25 years. Shermer hoped someday to match Gould’s record of producing 300 consecutive columns. That goal would elude him.

. . .

“I started to see the writing on the wall toward the end of my run there,” Shermer told me. “I saw I was being slowly nudged away from certain topics.” One month, he submitted a column about the “fallacy of excluded exceptions,” a common logical error in which people perceive a pattern of causal links between factors but ignore counterexamples that don’t fit the pattern. In the story, Shermer debunked the myth of the “horror-film curse,” which asserts that bad luck tends to haunt actors who appear in scary movies. (The actors in most horror films survive unscathed, he noted, while bad luck sometimes strikes the casts of non-scary movies as well.) Shermer also wanted to include a serious example: the common belief that sexually abused children grow up to become abusers in turn. He cited evidence that “most sexually abused children do not grow up to abuse their own children” and that “most abusive parents were not abused as children.” And he observed how damaging this stereotype could be to abuse survivors; statistical clarity is all the more vital in such delicate cases, he argued. But Shermer’s editor at the magazine wasn’t having it. To the editor, Shermer’s effort to correct a common misconception might be read as downplaying the seriousness of abuse. Even raising the topic might be too traumatic for victims.

The following month, Shermer submitted a column discussing ways that discrimination against racial minorities, gays, and other groups has diminished (while acknowledging the need for continued progress). Here, Shermer ran into the same wall that Better Angels of Our Nature author Steven Pinker and other scientific optimists have faced. For progressives, admitting that any problem—racism, pollution, poverty—has improved means surrendering the rhetorical high ground. “They are committed to the idea that there is no cumulative progress,” Shermer says, and they angrily resist efforts to track the true prevalence, or the “base rate,” of a problem. Saying that “everything is wonderful and everyone should stop whining doesn’t really work,” his editor objected.

Shermer dug his grave deeper by quoting Manhattan Institute fellow Heather Mac Donald and The Coddling of the American Mind authors Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, who argue that the rise of identity-group politics undermines the goal of equal rights for all. Shermer wrote that intersectional theory, which lumps individuals into aggregate identity groups based on race, sex, and other immutable characteristics, “is a perverse inversion” of Martin Luther King’s dream of a color-blind society. For Shermer’s editors, apparently, this was the last straw. The column was killed and Shermer’s contract terminated. Apparently, SciAm no longer had the ideological bandwidth to publish such a heterodox thinker.

Sorry for the long quote, but this gives you a flavor of how the magazine radically changed. Far from being a place where ideas can be examined and debated, the magazine fired a writer of nearly 20 years for suggesting that society should be color-blind.

Accepting radical orthodoxy was a prerequisite for employment at a once-great institution.

Before the late 18th century, Western science recognized only one sex—the male—and considered the female body an inferior version of it. The shift historians call the “two-sex model” served mainly to reinforce gender and racial divisions by tying social status to the body. (6/7) pic.twitter.com/x8KZ5rEaeW

— Scientific American (@sciam) August 24, 2022

Of course Scientific American is hardly the only publication that took this turn over the past few years. The election of Donald Trump broke the minds of many a person, and no group of people is more likely to become zealous advocates of kooky causes than the intellectual class. University professors, teachers, writers, public intellectuals...you name it, they went crazy and the crazy has metastasized into into a cancer that is eating up everything.

Telling scientists and science writers to "stay in our lane" is a tactic to silence people with relevant expertise from weighing in on divisive issues. Scientific American is committed to explaining the world around us—that means every lane is our lane. https://t.co/bmIOGs5ZKh

— Scientific American (@sciam) November 13, 2022

Including scientists and Scientific American. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters even had an article explaining why objectivity should be subordinated to social justice. One of the first pieces I ever wrote here was about that one. Good times.

Of course, nobody—almost literally—reads the Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, and over the years, most of us have picked up Scientific American, which has been incredibly authoritative and influential.

And it is a total mess.

Pundits are weaponizing disgust to fuel violence, and it’s affecting our humanity https://t.co/To4TBuDbSO

— Scientific American (@sciam) November 13, 2022

Meigs, in his essay, points to the George Floyd riots as the moment when a rotting tower that was once scientific objectivity collapsed as if an earthquake hit--and no doubt he is right about that. All the structural support that prevented scientific opinion from blowing in the wind had already rusted away, so when a strong gust came along it just collapsed.

But the rot began many years ago. Pursuing truth is more attractive in rhetoric than in practice, and causes like climate science have given scientists license to exaggerate, disseminate, use virtue signals, and follow the money. Scientists have never been pure because, well, they are human. But critical theory, social justice, and the ideological witch's brew that has taken over academia have licensed constant outright deceptions.

Like insisting that the gender binary was invented in the 18th century as if Genesis had never been written and human beings haven't been mating since the dawn of time. People have known about human sexuality as long as there have been humans.

Not according to Scientific American, though, because the trans movement decreed otherwise.

Serendipitously Scientific American's new editor took the helm right as COVID hit and the George Floyd riots raged, and it was perfect timing for the new editor.

The DEI worldview took over our institutions slowly, then all at once. Many on the left, especially journalists, saw Donald Trump’s election in 2016 as an existential threat that necessitated dropping the guardrails of balance and objectivity. Then, in early 2020, Covid lockdowns put American society under unbearable pressure. Finally, in May 2020, George Floyd’s death under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer provided the spark. Protesters exploded onto the streets. Every institution, from coffeehouses to Fortune 500 companies, felt compelled to demonstrate its commitment to the new “antiracist” ethos. In an already polarized environment, most media outlets lunged further left. Centrists—including New York Times opinion editor James Bennet and science writer Donald G. McNeil, Jr.—were forced out, while radical progressive voices were elevated.

This was the national climate when Laura Helmuth took the helm of Scientific American in April 2020. Helmuth boasted a sterling résumé: a Ph.D. in cognitive neuroscience from the University of California–Berkeley and a string of impressive editorial jobs at outlets including Science, National Geographic, and the Washington Post. Taking over a large print and online media operation during the early weeks of the Covid pandemic couldn’t have been easy. On the other hand, those difficult times represented a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for an ambitious science editor. Rarely in the magazine’s history had so many Americans urgently needed timely, sensible science reporting: Where did Covid come from? How is it transmitted? Was shutting down schools and businesses scientifically justified? What do we know about vaccines?

She decided that Scientific American was a great platform to shape America's political debate. As with every authority in the United States, she used her power to propagandize. It was a long time coming, but when it did, nobody in power held back.

What happened in newspapers, the intelligence community, the FBI, and every institution in America happened in science and Scientific American. "Democracy Dies in Darkness" was the distillation of it all: we know the truth, and will say anything to make you believe and act on it.

Several prominent scientists took note of SciAm’s shift. “Scientific American is changing from a popular-science magazine into a social-justice-in-science magazine,” Jerry Coyne, a University of Chicago emeritus professor of ecology and evolution, wrote on his popular blog, “Why Evolution Is True.” He asked why the magazine had “changed its mission from publishing decent science pieces to flawed bits of ideology.”

“The old Scientific American that I subscribed to in college was all about the science,” University of New Mexico evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller told me. “It was factual reporting on new ideas and findings from physics to psychology, with a clear writing style, excellent illustrations, and no obvious political agenda.” Miller says that he noticed a gradual change about 15 years ago, and then a “woke political bias that got more flagrant and irrational” over recent years. The leading U.S. science journals, Nature and Science, and the U.K.-based New Scientist made a similar pivot, he says. By the time Trump was elected in 2016, he says, “the Scientific American editors seem to have decided that fighting conservatives was more important than reporting on science.”

Scientific American’s increasing engagement in politics drew national attention in late 2020, when the magazine, for the first time in its 175-year history, endorsed a presidential candidate. “The evidence and the science show that Donald Trump has badly damaged the U.S. and its people,” the editors wrote. “That is why we urge you to vote for Joe Biden.”

At this point, you should distrust anything you read from any authority, not because everything is a lie, but because everything might be a lie or so packaged as to create a Narrative. There are still decent writers, scientists, reporters, entertainers, and academics.

But they are the outliers, getting pressured, silenced, canceled, and harassed. I know quite a few academics who have opted out and retired.

The thing is, people in the vast middle of our society, just trying to live a decent life, don't obsess about these things. They have always felt that they could reliably outsource most of the fact-checking and even thinking about many issues to rational authoritative sources. It's not like you can be informed on everything, and issues such as physics, chemistry, biology, and medicine are not exactly easy to pick up.

You have to trust people, otherwise you can't even be sure that Moscow exists or that the moon isn't just a big flashlight in the sky.

And you really can't be sure that the vaccine you took is safe and effective.

In losing Scientific American and all the other formerly great institutions, we have lost a pillar of our civilization. It is easy to underestimate the importance of social trust, and the only thing worse than not having institutions you can trust is trusting institutions you shouldn't.

Such as Scientific American.